Air Raid: How an Offensive Revolution Led to the Demise of the Running Back

And what comes next for those running backs.

On a warm evening in Lubbock, Texas, the Masked Rider gallops out of the tunnel on a black steed, whipping the crowd into a frenzy. Michael Lewis hears the roar from the locker room, where his eyes are locked on the head coach.

It’s 2005, and Lewis's most recent book, Moneyball, has kick-started the world’s obsession with analytics. Lewis told the story of Billy Beane, the manager of the Oakland A’s, who abandoned the wisdom of old-school scouts for the advice of 20-something-year-old stats geeks. The book was a New York Times bestseller, brought to the screen with Brad Pitt playing Beane and Jonah Hill playing one of the geeks.

It was Lewis’s interest in the more radical characters in sports that led him to Lubbock. The Texas Tech Red Raiders had just gone from the runt of Texas college football to the best college offense ever. The team comprised low-grade recruits left over after Texas, Alabama, LSU, and Oklahoma finished filling out their rosters. The way the Red Raiders played also screamed Moneyball. The team took every assumption about how football was supposed to be played, balled it up, set it on fire, and tossed it out the window.

Texas Tech didn’t use an offensive line in the traditional sense. They set up their blockers a few feet apart from each other across the line to allow for better throwing lanes. Texas Tech also didn’t believe in punting the football. As quarterback Cody Hodges explains, “Most offenses on fourth down are coming off the field. On fourth down we expect a play to be called. Because we haven’t scored yet.”

But most strikingly, Texas Tech threw the ball a lot. The average college team passed around 47% of the time in the ‘05 season. That season, Texas Tech threw the ball 70% of the time, the most in the NCAA.

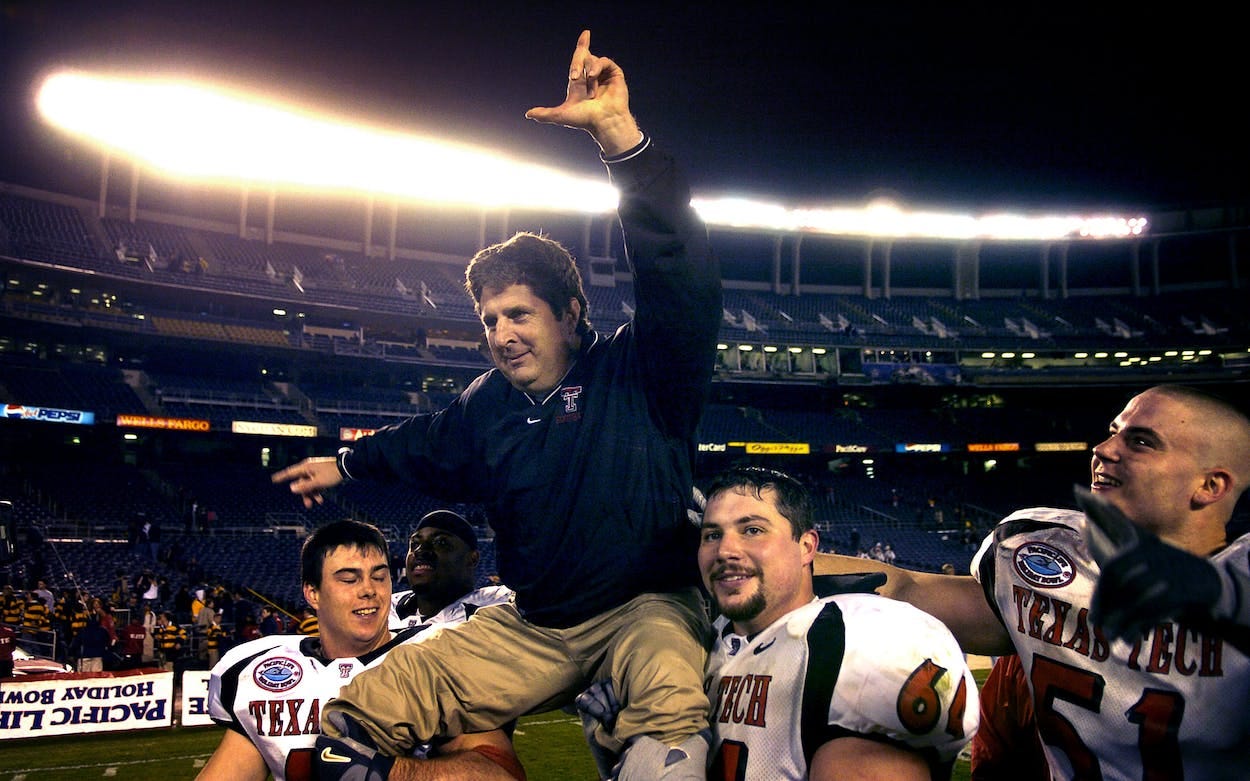

The mastermind behind these changes, and the man who Lewis had come down to Lubbock to see, was Mike Leach. Leach’s path to the job at Texas Tech was a winding one. Unlike almost every other coach in the country, he never played a snap of college football. Leach went to BYU and then Pepperdine for law school, where he graduated near the top of his class. Facing the prospect of a career in law, Leach instead decided to be a college football coach.

The job wasn’t a natural fit from a personality perspective. The traditional college football coach was a drill sergeant. Leach was more of a free spirit. He walked around campus wearing flip-flops and t-shirts. The Texas Tech strength and conditioning coach once spotted Leach weaving across Main Street on in-line skates. Skating was one of Leach's more normal pastimes, which included studying and lecturing unsuspecting football players on Jackson Pollock, chimpanzees, and, most notably, pirates.

Twenty years after he started his coaching career at College of the Desert (yes, I also had to Google it), Leach was the head coach at Texas Tech and the architect of the sport's most prolific offense. Texas Tech’s unorthodox, pass-heavy attack was called the “Air Raid Offense.” The core belief of the Air Raid was simple: offenses should force defenses to cover as much space as possible on the football field. Leach put five wide receivers across the formation, spreading the defense out width-wise. As the quarterback caught the snap, the receivers ran deep and stretched the defense length-wise. Although Leach’s receivers were never five-star talents, Leach always ensured they were very, very fast. In seconds, Leach’s offense bent and twisted defenses in ways they were not built to bend and twist. What resulted was open space, the oxygen for the Red Raiders’ offensive explosions.

Over the past 15 years, Leach’s Air Raid went from a fringe belief by a radical coach to a foundation of the NFL passing game. The first signs of the Air Raid in the NFL lead back to 2007 when Wes Welker, a walk-on wide receiver under Leach at Texas Tech, introduced the concept to Tom Brady and Bill Belichick in New England. Notably, the Patriots were undefeated in that 2007 regular season. In recent years, Air Raid quarterbacks like Jared Goff and Kyler Murray have been drafted in the first round to run the offense in the pros. Passing in the NFL is now as effective as ever, and Air Raid concepts pioneered by Leach are present in nearly every NFL playbook.

But despite all the success, the Air Raid revolution hasn’t been roses for all involved. Along with the introduction of new Air Raid ideas has come the questioning of some more traditional beliefs. Chief among these questions is one that Leach was asking 15 years ago at Texas Tech: If the goal on offense is to expose open space, why do teams ever run the football? As Lewis remarks in his profile on Leach, “The trouble with running plays, as Leach sees it, is that they clump players together on the field – by putting two of them, during a handoff, in the same spot with the ball. ‘I’ve thought about going a whole season without calling a single running play,’ Leach says, only half-joking.”

The RBs Don’t Get Paid

NFL GMs have probed this question of whether football still needs the handoff, not with their words in a press conference, but with their contract offers to running backs in free agency. The past two winners of the NFL rushing title, Josh Jacobs and Jonathan Taylor, both threatened to hold out this season after their teams refused to extend them long-term contract offers. Saquon Barkley, one of the NFL’s brightest stars, was offered the one-year franchise tag by his team and threatened to sit out the season. He earned a one-year deal worth $11m, measly when compared to the rest of the league’s elite players. Worried by these developments, the league’s top backs even hosted a Zoom call (organized by Chargers star Austin Ekeler, who was also not extended a long-term deal) to discuss possible strategies for retaining value in this post-running back market.

However, while the issue of declining running back pay has reached a fever pitch this summer, when we look at the data, we can see that this trend has been simmering for years.

We can measure a player's value to their franchise by how much they are paid. Every team has a set amount of money they can pay players each year, which is determined by the league’s salary cap. We can use the percentage of the salary cap that franchises allocate to each position as a measure of how valuable they view that position to winning. To understand how teams have valued a position over time, we can look at the largest deal by salary cap utilization at the position for each season. This “market-setting” deal will indicate how an elite player in the position is valued in a given year.

In plotting out the largest running back contract each year by cap utilization, we can begin to visualize their decline in value. In the late ‘90s, running backs like Emmitt Smith and Barry Sanders were the centerpieces of their offenses and commanded around 15% of the salary cap. Today, elite backs can expect to get less than half of that.

Now, let’s contrast that with each season’s market-setting quarterback contract.

Nearly every year since 2006, the proportion of salary cap allocated to elite quarterbacks has increased. That trend accelerated in 2020 when Patrick Mahomes signed a (then) monster ten-year, $450m contract with the Chiefs that moved the league’s quarterback market up over 20% of the salary cap, where it has stayed every year since.

Mahomes was a relatively unknown prospect through high school. As a junior at Whitehouse in East Texas, Mahomes’s tape found its way into the hands of Kliff Kingsbury, then the offensive coordinator at Texas A&M. Kingsbury knew a thing or two about quarterback play: he was a Heisman finalist in 2002 when he set the NCAA passing record at Texas Tech in Mike Leach’s Air Raid offense. When Kingsbury got the call in 2013 to take over the head coaching job at his alma mater, he went all in on Mahomes, getting him to put pen to paper and become a Red Raider. In Mahomes’s junior year at Tech, in the Kingsbury Air Raid, he set the NCAA passing record and was taken at #10 overall in the 2017 NFL draft by the Kansas City Chiefs. In 2019, Kingsbury would be names head coach of the Arizona Cardinals, the first Leach disciple to become an NFL head coach.

Air Raid Ripples

Seeing that quarterback pay is increasing and running back pay is decreasing, it’s worth asking if other positions are witnessing a shift in value. Seeing which positions are rising in value and which are declining can give us a more holistic view of how a more pass-happy league is changing the game. Let’s again look at the market-setting contract data, but this time for wide receivers, a likely beneficiary of the Air Raid Revolution.

Elite receivers have seen almost no increase in cap allocation for market-setting deals. In a league that values passing more than ever, how could the best pass catchers have not seen a jump in value?

A possible explanation strikes at the heart of Leach’s offensive revolution. While it is often simplified to be about passing, what Leach was really preaching was forcing the defense to cover as much space as possible. While a single receiver can do that more easily than a running back receiving a handoff, a modern, Leach-inspired NFL offense calls for paying a fleet of high-level receivers that stretch the defense in different directions. The data supports that idea: While a single elite receiver has seen a modest increase in value, the percentage of payroll dedicated to all receivers in the NFL has increased nearly 20% since 2013, when overthecap.com began keeping pay data by position.

Salary cap allocation has also moved to address the pass on the defensive side of the ball. Faced with more passing situations, money on the defensive end has begun to flow away from positions tasked with stopping the run, like linebackers and defensive tackles, and towards positions that impact the passing game. Edge rushers are some of the league’s highest-paid players, born out of a necessity to get to the quarterback quickly and limit the damage they can do down the field. Free safeties, key to pass coverage, make twice as much as strong safeties, who are more focused on stopping the run.

The NFL is a passing league, and player pay continues to reinforce that. The running back position is suffering from a fundamental issue: the traditional running play is less effective than a passing play, making running backs less valuable. The question is whether the running back will go the way of the fullback - nearly extinct across the league - or if they will find a new role in this new NFL.

The Future of the Position

Christian McCaffrey, the league’s highest-paid running back, is in motion from the backfield toward the sideline. Buccaneers safety Logan Ryan moves out to cover McCaffrey man-to-man, lining up across the line of scrimmage. San Francisco 49ers quarterback Brock Purdy takes the snap. McCaffrey begins to run down the sideline with Ryan in stride. McCaffrey feints inside, and Ryan bites, trying to jump a potential slant play and make an interception. That’s when McCaffrey explodes down the sideline, leaving Ryan in the dust behind him. Purdy makes the easy throw to the wide-open McCaffrey for a 30-yard TD.

Despite his designation as a running back, McCaffrey has always been comfortable catching the football. His father, Ed McCaffrey, was a top NFL wide receiver himself. Combining that talent with his elite athleticism and excellent game IQ (he went to Stanford, after all), the younger McCaffrey quickly became the league’s best back after being drafted by the Carolina Panthers in 2017.

While his excellence was clear in Carolina, it never really translated to much winning on an underwhelming Panthers team. That changed when the San Francisco 49ers sent a barrage of picks to Carolina to bring McCaffrey to one of the most innovative offenses in the league. Led by Kyle Shanahan, the 49ers subscribe to a notion of “position-less football” on offense. Their skill players move seamlessly across the formation, creating mismatches and exposing space. That idea was turbo-charged when the team added McCaffrey. The dynamic running back would often begin the play where running backs normally do, in the backfield, only to move out to the slot receiver position, to the end of the line as a pseudo tight end, or even all the way out wide as a traditional wide receiver, as he did for his touchdown against the Buccaneers.

In perfectly Leachian fashion, Shanahan has transformed McCaffrey from a talented running back into the NFL’s foremost weapon for exposing open space. McCaffrey’s departure from the running backs traditional utilization has allowed San Francisco to make him the focal point of their offense, something that running backs haven’t been since the days of Emmitt Smith and Barry Sanders.

It’s worth noting that Taurean Henderson - Texas Tech’s running back on the day Michael Lewis came to Lubbock to write about Mike Leach - thrived in the Air Raid to break the NCAA record for most receptions by a running back. If the future of the position is indeed a shift towards pass-catching, as Henderson and McCaffrey’s success suggests, we may soon chalk up the upheaval of the running back market to just another act in Mike Leach’s Air Raid revolution.

Downstream, younger players have also noted how effective McCaffrey has been in the 49ers system and wonder if his success is a blueprint for the future. Star Ole Miss running back Quinshon Judkins called the NFL running back market a “big concern” and remarked that he was working on expanding his skillset in preparation for the NFL: “I have a lot of receptions, a lot of [receiving] yards. I can not only be used in the backfield, but I can also be used in the slot as well. You can put me all over the field no matter what you need me to do as a playmaker. I think that as far as the next level, the way they’re doing those guys is because I feel like you can only do so much at that position.”

To adapt running backs to the modern game, it may be time to broaden their job description from ball carriers to playmakers. If it results in a league full of McCaffrey-esque weapons, it may not only save the value of the running back; it might just be the league’s next offensive paradigm shift.

Edited excellently by Greta Gruber