All-In: The Case for Swinging Big to Land Stars in the NBA

On the Lillard trade, the marginal benefit of star power, and why building a champion is a strong-link problem.

You would be forgiven if you thought that it was a typo.

“Breaking News: Damian Lillard traded to the Mi-”

Drafted out of Weber State in 2012, Lillard has grown into one of the NBA’s best players during his time with the Trailblazers. He is a perennial All-Star, one of the players in the league who can get you 30 points on any given night. His highlight reel is a montage of clutch, buzzer-beating threes, followed by Lillard motioning to his wrist in a nod to his catch-phrase “Dame-time.”

Fans across the league admired Lillard as one of the stars “doing it the right way.” While many of the league’s best players plotted to team up with other All-Stars to chase championships, Lillard remained faithful to the Trailblazers, reiterating time and time again that he wanted to retire as a Trailblazer.

But as the years wore on without any real title challenge, and the Trailblazers shifted from a fringe contender to a Western Conference basement-dweller, it became clear that Lillard was considering calling time on his tenure in Portland. The Portland-Lillard relationship came to a head on July 1st when Lillard demanded a trade, specifying the Miami Heat as his preferred destination.

Miami, which last season had shocked the league on the way to an NBA Finals appearance, was a piece away from being a serious contender. Heat fans flooded the internet with edits of Lillard next to Erik Spoelstra and Jimmy Butler as they began to celebrate his all-but-certain arrival.

But despite Lillard’s move to Miami looking a forgone conclusion, it didn’t happen right away. Then came the reports that the Trailblazers weren’t interested in the package Miami offered: a combination of draft picks and Tyler Herro. Portland insisted on a package that included either Jimmy Butler or Bam Adebayo, established players they knew they could flip to contenders for additional draft capital. A stalemate ensued. Miami, which felt they had leverage over the situation because Lillard made it clear he wanted to play in South Beach, stood firmly behind the Herro package, seeing a Butler deal as a non-starter and an Adebayo one as too great a price. Portland stood firm as well, willing to wait for a better deal as they shopped Lillard across the rest of the league. And as July turned to August and August to September, Lillard remained a Trailblazer.

And then somebody took a swing. The NBA world, as is custom, learned via Twitter.

“Breaking News: The Portland Trailblazers are trading guard Damian Lillard to the Mi…lwaukee Bucks.”

The league did a double-take, but yes, you did read that correctly. The Milwaukee Bucks, not the Miami Heat, acquired Lillard.

The price was steep. Lillard cost the Bucks Jrue Holiday, a key piece of their 2021 championship team, a first-rounder, pick swaps, and Grayson Allen, an important role player.

The deal threw the Bucks and the Heat, two teams at the top of the Eastern Conference, into sharp contrast. When faced with the huge asking price for Lillard, Milwaukee pushed the chips in, while Miami balked, opting to run things back with their young talent rather than swing for the fences and acquire a superstar.

Their responses pose two different answers to a question central to building NBA rosters: what is a superstar worth to a contender?

The NBA is A Strong Link Problem

Nate Silver explored the idea in a 2017 article prompted by the Celtics’ acquisition of Gordon Hayward. Silver wanted to know how impactful Hayward’s acquisition would be to Boston’s championship odds for the next season. What did he learn? First and foremost, nearly every NBA champion of the last 30 years was built around one of the best players in the league: Silver’s analysis went from 1985 to 2017, and of those 33 champions, 23 of them had one of the best three players in the league.

Even more compelling, however, is that Silver also shows us that most champions have multiple star players carrying the load: The average second-option on these teams was the 14th-best player in the league, and the third-option was the 37th-best player. To put that in context, this would mean that, on average, the second-best player on these championship teams was an All-NBA player, and the third-best player was just missing the All-Star Game. That’s a lot of star power.

To generalize this idea that stars win championships, Silver created a framework to measure each team’s “Star Points.” He found each NBA player’s CPM (Consensus Plus-Minus), a mash-up of different advanced stats that measure an NBA player's contribution to winning, and then tiered them into three levels of stardom: Alpha, Beta, and Gamma. Alphas are MVP-level players generally good enough to be the best option on a championship team. Betas are just below them, usually All-NBA (top-15) guys, but not quite vying for “best-player-in-the-league” status. Gammas are the tier below them, All-star level players but probably not “the guy” on a winning team.

Silver then assigned each qualifying player star points based on the tier they fell into: Alphas got three points, Betas got two, and Gammas got one. From there, Silver found the star points for every champion between 1985 and 2017 and calculated championship probabilities for NBA rosters based on how often teams at each star point value won the championship.

Let’s start by qualifying this analysis. Stars are not everything in the NBA when it comes to winning championships. Those role players who do the little things, like set screens and rotate on defense, do help their teams win. Coaching can be the difference between a team over-achieving or flaming out in the first round. This analysis isn’t saying that stars are the only things that matter; it’s just saying that stars probably matter a lot more than everything else. That means the championship probability metric we will use heavily here is helpful in broadly understanding which teams are contenders, but doesn’t consider finer points like coaching, depth, etc. That’s fine for this analysis, but you could get “truer” probabilities by using the Vegas odds, which factor everything in.

So, how do the results shake out? Having anywhere between zero and four star points gives us a very long shot at the championship. However, once we get to five points, there is a leap up to a nearly 10% chance at the title. Get to six points, and we have a 14% chance, or close to 1-in-7. After that? Adding star points to get to seven or eight points gives us a nearly 1-in-3 chance of winning a championship.

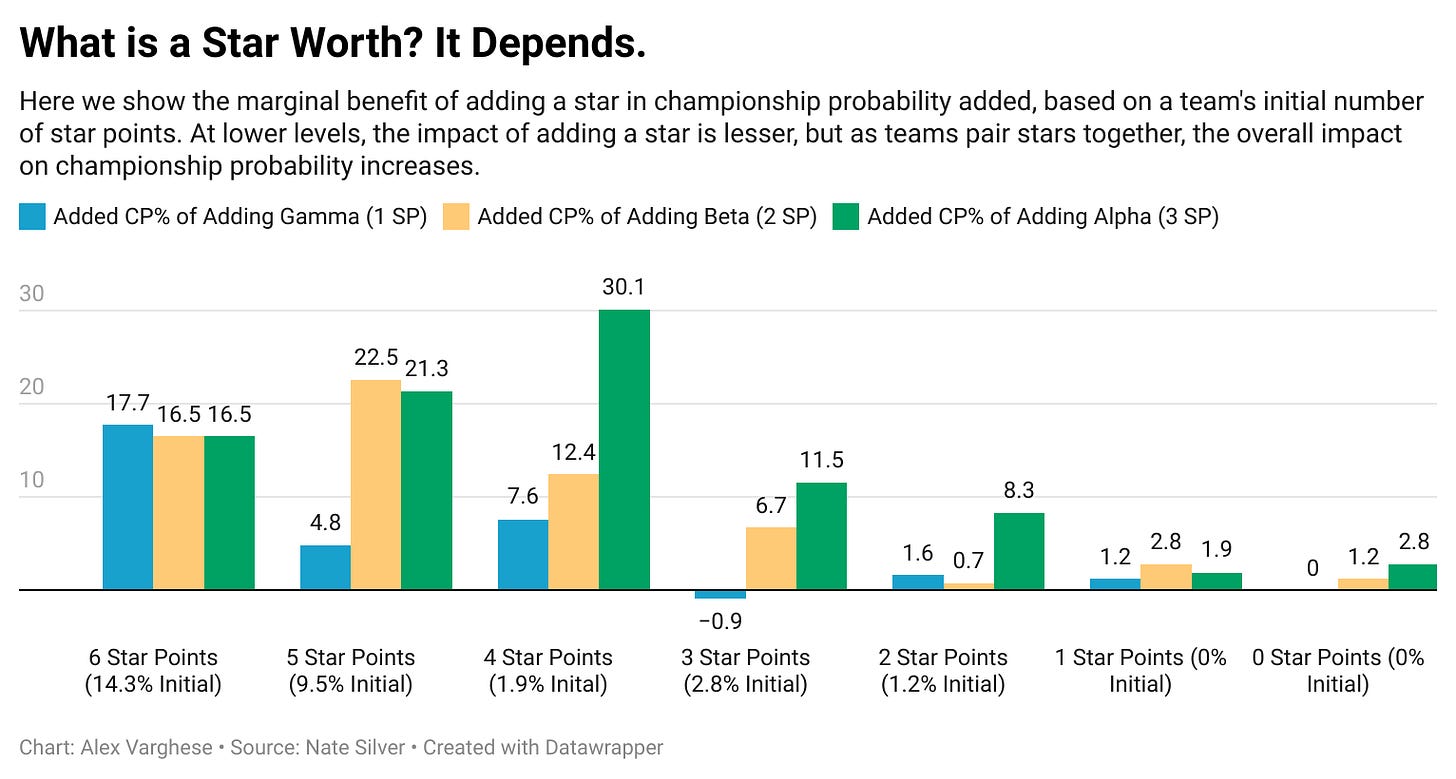

From these title odds, we can derive a key insight into the value of star players: Stars are worth more to teams already in contention. In other words, the marginal benefit of star points is variable. Adding an Alpha like Nikola Jokic or Giannis to a team with zero star points doesn’t change our odds of winning a championship much; we only move up to 2.8% championship probability. Meanwhile, adding that same Alpha to a team with four star points moves their title odds from 1.9% to 32%.

Adding a star when you’re a contender, somewhere between four to six star points, has a huge impact on your likelihood of winning a championship. That means teams in this pocket have a big incentive to go for it if they have the assets. Cashing in young players and draft picks for a star if you are somewhere between four and six points has an instant, massive return in an increased likelihood of winning a championship, and that’s why we’re all here in the first place.

Lurking behind this model is a more general concept - we’re approaching team building as a strong-link problem. As Adam Mastroianni explains on his excellent Substack, a strong-link problem is one where “overall quality is determined by how good the best stuff is, and the bad stuff barely matters.” These strong-link problems contrast with weak-link problems, where the overall quality of a solution is determined by limiting how bad the worst stuff is. The tradeoff between the two comes in how variable your outcomes are. A strong-link solution has more outliers, both good and bad, whereas a weak-link solution has more consistently average outcomes with a reduced chance of extremely high or low-end outcomes.

Classifying problems as either strong-link or weak-link is helpful because you address them in very different ways. To determine if we are in a strong-link or weak-link problem, we ask ourselves, “Are we hoping for highly variable outcomes that may yield an exceptional result, or is a consistent, average result preferred?”

For example, let’s say we regulate the airline industry. Success is our flights getting from point A to point B safely, every time; that is, nothing exceptionally bad happens. This is a situation where we want to reduce variance. The strong-link scenario, having a shot at the safest flight in history at the risk of potentially having a really unsafe flight (exceptional outcomes), is not a good tradeoff here. We want all the outcomes being very normal, safe flights. Flight safety is a weak-link problem: we focus on reducing exceptional outcomes and ensuring our worst flight is still a safe one.

Let's contrast that with how we solve the problem of building an NBA champion. Instead of the airline situation, where we want to avoid an exceptional outcome, we’re dealing with the opposite scenario: the only success is the one team winning a championship. To beat the other 29 teams, we need an exceptionally good outcome. Silver’s analysis shows us that we can maximize our chances of these exceptionally good outcomes by acquiring as much star power as possible, so we’ll build out that end of our team at the expense of our weaker links. This solution gives us a chance at some very high-end outcomes, but its variance also exposes us to a lot of very bad ones. One of our stars gets injured or has a string of poor performances, and suddenly, our team implodes. In a winner-take-all game, however, we understand that this variance is necessary to give ourselves a chance at the exceptionally good outcome we need.

State of the NBA

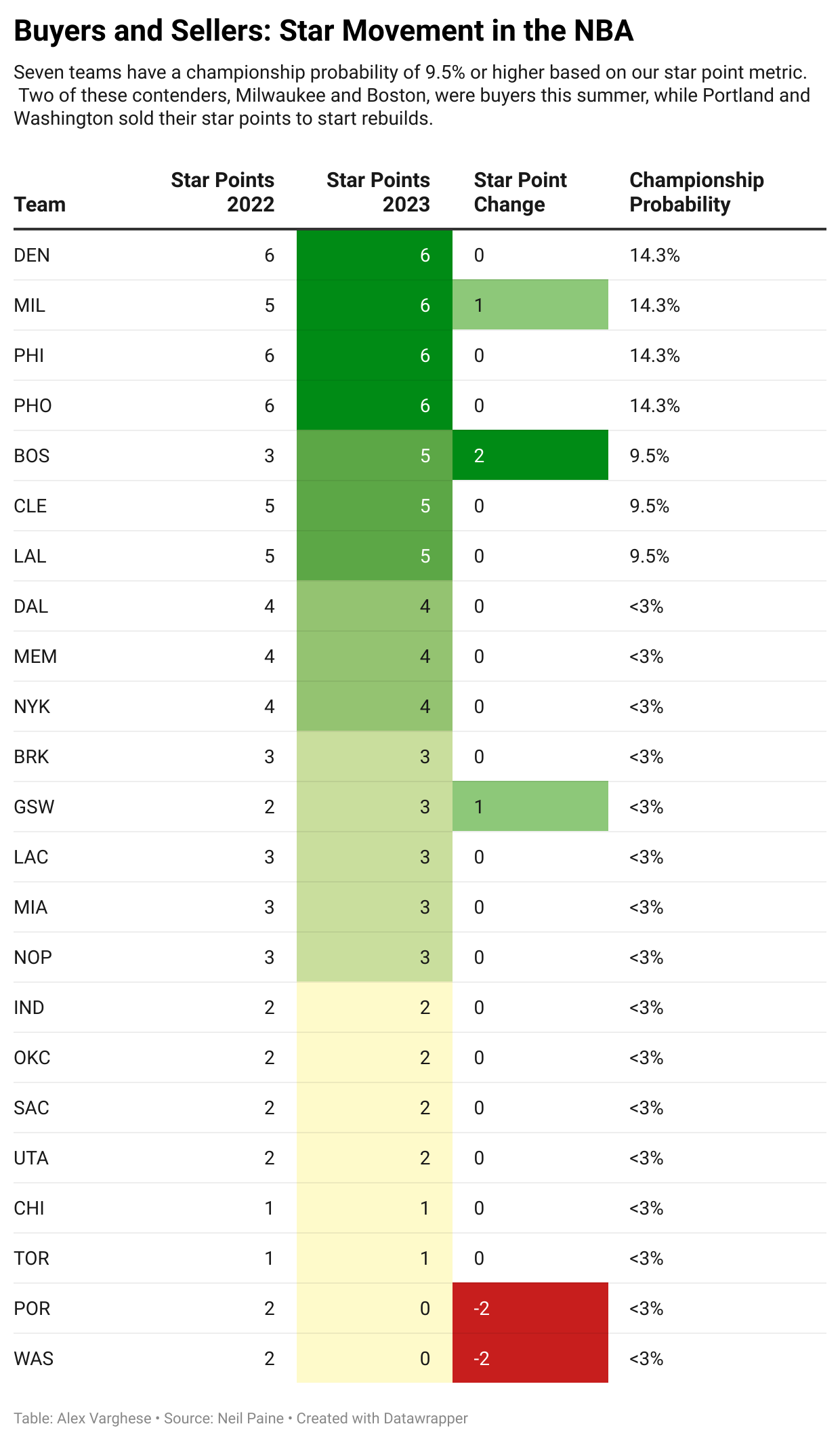

Armed with our improved understanding of team-building, let’s analyze all the star movement caused by the Lillard move from this offseason, which had ripple effects across the league. Thanks to Neil Paine, a 538 alum and author of another great Substack, we have this past year’s CPM numbers and can find the star points by team for the 2023 season. I’ll include a chart of 2023’s Alphas, Betas, and Gammas at the bottom of the piece.

Let’s begin with Boston. They are probably slightly underrated by this star point metric, but they had a great summer, acquiring two star points and moving up to a 1-10 shot for a championship. One of those points was Jrue Holiday, who Boston acquired from the Trailblazers shortly after being sent there in the Damian Lillard trade. Holliday rounds out this Boston team, getting them great defense and championship experience. Vegas agrees, putting the Celtics at +400, or a 20% probability, to win the championship.

How does a team have a good summer by trading stars away? They get a haul of future assets in return. Portland losing Lillard moved them from a 1.2% chance of winning the title to a 0% chance. They were never real contenders at two points and would’ve had to find three or four star points somewhere to compete now, a move they didn’t have the assets for. Instead, Portland became a seller over the summer and got back a treasure chest of possible future star points. In exchange for Lillard, the Trailblazers ended up with three first-round picks, two pick swaps, and four players with star potential: Deandre Ayton, Malcolm Brogdon, Robert Williams, and Toumani Camara. Losing the franchise’s best-ever player hurts, but turning Lillard into such a wide range of assets lays fertile ground for a future contender in Portland.

And this brings us back to the other side of the Lillard trade, where Milwaukee went all-in, and the Heat decided to hold.

Milwaukee’s move for Lillard moved their star point-driven championship probability from 9.5% to 14.3%. Vegas likes the Bucks even more: they have them tied with the Celtics for the best odds to win the championship at +400, or 20%. Miami, meanwhile, stays stuck at three star points, where our star point analysis suggests that their championship probability is around 3%. Vegas concurs, listing their odds at +3000, or 3.23%.

If you’re Miami, it’s hard not to wonder what could have been. Adding Lillard in exchange for Adebayo would have moved the Heat to five star points and made them a serious contender. It also would have kept Lillard out of Milwaukee, who the Heat will have to find a way to sneak past if they hope to make it back to the Finals this season.

Miami will take solace in keeping their core group together. They’re betting on Adebayo’s output rebounding to its 2022 level, where he was a Gamma-level player. Perhaps Tyler Herro, who the Heat dangled in front of the Blazers as a potential future star, will also make the jump. If the stars align (pun intended) internally for the Heat, they may well get to the five point mark in-house, which follows their team-building philosophy in the post-LeBron era.

Unless these pieces fall into place, however, the Lillard trade may haunt the Heat as the big swing they should've taken, but didn’t.

Edited Excellently by Greta Gruber

If you enjoyed this piece, please like, subscribe, restack, and share it with a friend using the buttons at the bottom of the piece.

Here are the 2023 Star Points, based off of Neil Paine’s CPM numbers: