Assets: The Gamble at Chelsea

On portfolios, player development, and Chelsea's compounding future

Roman Abramovich’s first job was as a toy salesman, selling plastic dolls and rubber ducks from his Moscow apartment.

Ultimately, it was the gasoline and steel businesses, not the dolls or ducks, that earned Abramovich the $14.5B that made him one of the world’s richest men. Along the way, Abramovich went from a toy-seller to one of the world’s foremost toy collectors. He owns an $11M Ferrari FXX, of which only 29 were produced. His art collection includes work from Mondrian to Matisse, and is valued around $1B. The Russian also financed the construction of the $700M Eclipse, the largest of the 16 yachts in his fleet.

But none of Abramovich’s other playthings rivaled the Russian’s crown jewel: Chelsea Football Club. Abramovich purchased a struggling, debt-ridden Chelsea in 2003 for $75M. Before the team played a game under their new owner, he spent over $125M to bring in star players like Claude Makélélé, Hernán Crespo, and Damien Duff. The following season, Abramovich appointed José Mourinho, the self-anointed “Special One”, as manager. Mourinho rewarded Abramovich’s heavy spending by winning the Premier League in 2005, the club’s first league title in 50 years.

The ‘05 Premier League title would be the first of 18 major trophies raised at Chelsea in 20 years under Abramovich. Throughout that run, the club was a revolving door for soccer’s most distinguished players and managers. A pattern emerged at Chelsea: first, buy the world’s finest players at the peak of their powers, often for staggering transfer fees and on expensive contracts. Next, appoint the world’s most sought-after manager to lead them. Together, that group would generate a few years of massive success, followed by a dramatic decline as those players who arrived in their prime began to decline in their 30s, and the manager’s game plans became tired. At this point, Abramovich would clean house - he bought new players, hired a new manager, and started the cycle again.

Even when Chelsea were maximizing TV and commercial revenues by competing for the Premier League and Champions League titles, running the club this way was not remotely profitable. Yet, it was - for Abramovich, at least - sustainable. The Russian was so wealthy that he could comfortably eat the operating losses that came with constantly furnishing the club with top players at premium prices. Chelsea was not so much a business as the world’s most expensive hobby for one of its wealthiest men. While Manchester United was raising capital through public offerings, and Moneyball-influenced American owners were taking over Liverpool, Chelsea remained uniquely unconcerned with profitability.

The Abramovich era ended in May of 2022. Earlier that year, when Russia invaded Ukraine, Abramovich was put on a list of Russian oligarchs sanctioned because of their close ties to the Kremlin. The British government forced Abramovich to sell Chelsea. The buyers were a consortium led by Todd Boehly and private equity firm Clearlake Capital, who purchased the club for $5.2B.

Boehly is the public face of the new ownership group. The American has a good pedigree as part owner of the L.A. Dodgers and L.A. Lakers and an endearing, if at times naive, enthusiasm for soccer. Besides raising sufficient capital to buy the club, an impressive feat on its own, Boehly’s bid was seen as a good option for Chelsea because of his data-driven approach to ownership. That philosophy, along with the presence of Clearlake Capital, a private equity firm whose typical investment timeline hovers around seven to ten years, sent a clear message about the future of the club: Chelsea the toy would become Chelsea the asset.

Chelsea, the Asset

It’s clear where the opportunity lies in Chelsea as an investment: Because the club was not being run as a business, it lost a lot of money. From 2013 to 2022, Chelsea was over £383M in the red - compared to profits of £153M for Liverpool and £203M for Tottenham over the same period. The objective for the new owners is to turn Chelsea into a sustainable business like these latter examples.

A big club’s formula for profitability is something of a balancing act. Still, it has been executed well across the UK by a few teams, including Tottenham, Manchester City, and Liverpool. Clubs must drive revenues, primarily from broadcasting appearances and sponsorship deals, while limiting costs, the largest of which are player transfer fees and wages. The way to drive those revenues is simple: win more soccer games. Teams competing at the top of the Premier League get more airtime, meaning more broadcast revenue. Playing in the Champions League - the knockout-style tournament of Europe’s elite - is worth, on average, over €100M to English clubs between additional broadcasts, ticket sales, and prize money.

The primary role of ownership in helping their clubs compete and, in turn, drive revenues, is to buy the right players in the transfer market. The tension in profitability for soccer clubs lies in that ownership must buy good enough players to win games and drive revenues while keeping the costs of acquiring and retaining those players as low as possible. This latter part of the equation is one that Chelsea under Abramovich largely ignored, so while they were successful on the field, the club ran at a considerable loss.

Large clubs utilize a few popular transfer models to drive profitability. Liverpool, run by Fenway Sports Group (FSG), invests heavily in analytics to identify undervalued players and get revenue-driving play on the field at a relatively low cost. Manchester City employs a more expensive squad but maximizes it with such excellent results that they’re generating the revenue to offset the spending. While less successful on the field than these first two examples, Tottenham has also become profitable over the last several years by keeping a low wage bill that still performs on the field and drives traffic to their new stadium.

But nearly two years into Boehly and Clearlake’s reign at Chelsea, the club’s transfer activity looks like nothing world football has seen before.

Over the first four transfer windows under Boehly and Clearlake, Chelsea has spent over £1B on transfers. The new owners have undertaken a complete overhaul of the squad, offloading a boatload of players and signing an even larger and more expensive group to replace them.

The owners at Chelsea have also targeted a particular profile in their new signings: they are young. Of the 28 players that Chelsea has purchased over these first four windows, the average age has been 21.3 years old. Throughout those four windows, the club brought in a stream of Europe’s finest young players at premium prices, highlighted by the record-breaking purchases of Enzo Fernández (€121M) and Moisés Caicedo (€106M).

This approach, assembling an entire squad of bright young players to kickstart a rebuild, has never been done before, either at this scale or by a club of this size. It has also looked unintuitive - if the goal is to bring a sustainable business model to Chelsea, how could the owners achieve that by spending even more money than the club did under Abramovich?

Amplifying the confusion has been the slow early returns of the project - Chelsea finished tenth in the first season under Boehly and currently sits in eleventh - the club, from the players to the manager, and most of all, ownership, have come under extreme scrutiny.

Criticism comes with the territory when you are in the soccer business in England. The Premier League is the country’s soap opera, and rumors of transfers, hirings, and firings dominate the back pages of every paper, a form of entertainment that rivals the on-field product. But cut through the noise, and the reality at Chelsea is that whether this novel transfer strategy is carefully calculated or arrogant or both, Chelsea today are walking on untrodden ground.

What exactly is Chelsea banking on in their unorthodox transfer strategy - and can it work?

Beyond the Transfer Fee

To answer that question, we’ll begin with the most basic yet misunderstood component of player acquisitions: the transfer fee.

They are the big red numbers in social media graphics or on the front page of the tabloids. Once a player is purchased, his transfer fee follows him for his entire stay at the club, a baseline to use in lauding him as a great value or labeling him as a flop. Yet, transfer fees often mislead soccer fans about the true nature of the investment in a player.

Despite how the transfer fee is presented - as a lump sum sent from the buying club to the selling club for a player’s services - this is not how transfer fees are actually paid or represented in accounting books. In reality, a purchased player's transfer fee is amortized (or spread evenly) across the length of his contract*. When you add the player's amortized annual fee to his wages, you get a player's annual cost. It’s important to shift our thinking of investment in a player from their transfer fee to their annual cost because it fully encapsulates what a club is actually paying for that player.

To put this in perspective, consider this figure showing the annual cost of recent signings under the age of 25 by the Premier League’s Big 6:

While Chelsea have spent a lot of money on these headline-grabbing transfer fees, they’ve kept their annual costs in line with, and in many cases, below, their competitors by amortizing those fees on longer contracts with lower wages. Chelsea has gotten players to sign these deals because of their age; young, unproven commodities are more inclined to sign extended contracts for slightly lower wages to hedge the uncertainty in their development.

These long, spread-out contracts minimize annual costs and are a crucial tactic in Chelsea’s overall transfer strategy. While Chelsea ultimately is on the hook for the entirety of the amortized transfer fee plus wages, spreading them out over a long period to reduce annual costs has several benefits. These include helping Chelsea stay compliant with FFP (Financial Fair Play) standards*, which are effectively a salary cap, and reducing the effect of each player on the club’s annual cash flow.

The third and most interesting aspect of this tactic is that it locks these players into Chelsea for a really long time. The benefit to that long time horizon is that if the global transfer market is undervaluing youth players, then securing these players early and through their prime could result in them looking like deals later on in their careers, while also increasing Chelsea’s leverage to sell these players at high fees. Conversely, when any of these players that Chelsea brought in on long contracts don’t turn out, the club is stuck paying their annual cost for years afterwards.

That risk makes it all the more interesting that Chelsea made so many of these deals. On the surface, the club's decision to bet so heavily in such an unorthodox direction suggests a kind of arrogance - Boehly and Co. showing up in England and declaring that they know something that these long-standing, historic clubs do not.

But considering these tactics together - the long, spread-out contracts and the high volume that Chelsea acquired them in - they contribute to an overall vision, albeit an unconventional one. Boehly and Clerlake are executing a strategy right out of a finance playbook: They are building an investment portfolio at Chelsea, where the assets are the club's young players.

Gambling on Development

One of the main benefits of portfolios is that they help shield their investors from large variances in any one of their assets. Any mitigation of risk is especially attractive to Chelsea because the assets they are dealing in - young men between 18 and 23 - are incredibly volatile. Some will undoubtedly flame out, either under the weight of expectation, the unfamiliarity of new surroundings, or through bad luck. On the other hand, some players will thrive at the club and outperform their expectations. To shield themselves from bad outcomes, the club has acquired a bunch of these volatile players to diversify its portfolio. As the size of the portfolio grows, the club would in theory increase the likelihood of a normal developmental return via regression to the mean.

Take, for instance, two wingers acquired during the club’s recent spending spree, Mykhailo Mudryk (£75M, £14.6M annually) and Cole Palmer (£47M, £10.61M annually). Mudryk has started slowly at Chelsea, struggling to produce and seeing limited game time. He’d be an example of a player whose current growth curve looks below average. Palmer, in contrast, has exploded onto the scene at Chelsea, sitting near the top of the Premier League in both goals and assists. Palmer is an example of a player outperforming the expected development curve. Chelsea is hoping that for every Mudryk underperforming, there will be at least one Palmer to bring the group's overall development back to average or better.

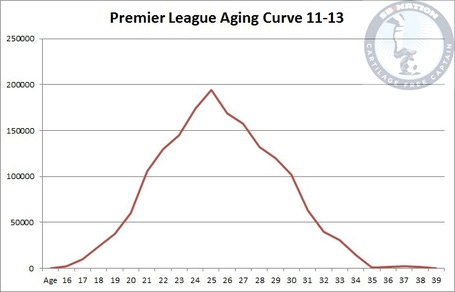

And, on paper, the outlook for a group of Chelsea’s pedigree is very bright. Consider a standard development curve for Premier League players, as shown below from Michael Caley’s work at Cartilage Free Captain.

The portfolio at Chelsea should be rapidly developing. Considering that these are some of the finest young prospects in the world, it’s reasonable to expect that the Chelsea portfolio’s curve should be even steeper, with a higher peak and longer plateau, than this development curve for the average Premier League player. And while no one would suggest while sitting in eleventh place that the project is on schedule, there remains hope that, on the aggregate, the portfolio will still develop to its potential.

But Chelsea should be concerned about the possibility that because they bought developing young players in this portfolio style, average developmental returns for the players are far from guaranteed. The reason is that the risk-minimizing aspect of portfolios, regression to the mean, relies on the assets at Chelsea - the developing, young players - developing independently. But because Chelsea is composed of only these young players, they are actually extremely dependent on one another.

This is where Chelsea are really in uncharted waters. Never has a big club thrown this many prospects into the deep end of a rebuild. The traditional method of player development takes place alongside mature, experienced players, not in place of them.

For the best example of this traditional development model, look across the English Channel to Borussia Dortmund. Dortmund has earned a reputation as a “finishing school” for some of Europe’s finest young talents. Their alumni over the past few years include Ousmane Dembélé (£115M), Jadon Sancho (£73M), and, of course, Erling Haaland (£51M via release clause, market value: £128.3M), and Jude Bellingham (£88M).

Bellingham and Haaland, the two most valuable players on the planet according to Transfermarkt, even played together in the same Dortmund team in the 2021-2022 season. Combined with Dortmund's reputation for developing so many young talents in recent years, it would perhaps have you believe that they, like Chelsea, were fielding a portfolio of young prospects that year.

Except the team actually looked like this:

The average age of the most used eleven at Dortmund was around 26 years old. The club surrounded their emerging young talents with mature, experienced players. While it may be hard to quantify the benefits that Haaland and Bellingham gained from playing in this environment, it’s easy to imagine them. Bellingham played through-balls to intelligent runs from proven goalscorers Marco Reus (33) and Julian Brandt (26). Haaland was getting a steady supply of chances, coming as crosses, through-balls, or via combinations from veteran playmakers.

This development style also comes with benefits that, while less tangible, may be equally important in helping players reach their potential. This Dortmund team finished second in the Bundesliga, operating at a level befitting the talents they were developing in Haaland and Bellingham. Along with getting to practice the technical and tactical sides of the game, these two young players were able to learn some of soccer’s soft skills as well, like professionalism, discipline, and, most importantly, how to win.

Success stories in this vein - young players growing up gradually alongside older, more seasoned ones - are not limited to Dortmund's massive successes, either. Look through the world's most valuable young players right now, and it’s the same story again and again: Lamine Yamal at Barcelona has Robert Lewandowski and İlkay Gündoğan in support. Vinicius Junior went from a prospect to a star next to Toni Kroos, Luka Modrić, and Karim Benzema at Real Madrid. Evan Ferguson at Brighton and Phil Foden at Man City have shown tremendous growth in veteran teams over the past season - the list goes on.

A Compounding Future

In trying to hedge their player development, Chelsea have created an environment without the proven commodities traditionally leaned on in the growth of young, promising players. Not only are these 18- to 23-year-olds expected to develop into stars, but they are also the foundations for the development of the players alongside them.

And here lies the real gamble Boehly and Clearlake are taking at Chelsea: They built an investment portfolio of players and the development of these players are interlinked and could very well compound, either positively or negatively. Mudryk and Palmer aren’t two independently developing players. Palmer's performance impacts the development of Mudryk, and vice-versa.

You can see a microcosm of Chelsea’s youngsters' tendency to swing towards extreme outcomes week to week in their inconsistency. This group has had excellent performances, including two entertaining draws against Manchester City, the best team in Europe, and a dismantling of Aston Villa in the FA Cup. But sandwiched between those great showings were poor ones, like the losses to Wolverhampton and Liverpool.

In each game, you see the cascading effects the young players have on each other. In the Manchester City game in February, Axel Disasi made a goal-saving tackle and jumped to his feet with a fist pump and a roar. The center-back inspired the team with his excellent performance, and the rest of Chelsea’s young prospects raised their level to compete with City. Here is the upside of the youth gamble - young, talented players rise to the occasion with performances that reflect their potential and positively influence the other impressionable talents around them.

But then you see Wolverhampton steal an early goal against Chelsea, and when one head drops in despair, the group lacks the leadership or resilience to prevent an avalanche of poor performances. There is no center at Chelsea, no “Steady-Eddys” for the players to rely on consistently, and so every week, the team is sent to one end of the high-variance outcomes inherent in young players.

In fairness to Boehly and Clearlake, they did, on some level, try to bring in experienced players to provide structure around their youth. However, Christopher Nkunku's injury woes, Raheem Sterling's poor form, and Thiago Silva's physical limitations have not provided the foundation, both in terms of performance and leadership, that the club would have hoped for.

Without the developmental guardrails of these more experienced players in place at Chelsea, the long-term development of Chelsea’s prospects are up to each other. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. These players are some of the finest young talents in Europe and are capable of playing like it. It does, however, open up Chelsea’s future to a lot of risk.

There are outcomes for Chelsea where their gamble pays off tremendously. They look like this: In the absence of experienced cornerstone players at Chelsea, the young players at the club develop quickly into prominent roles. A great example of this already at Chelsea is the aforementioned Palmer, who has filled part of the production and leadership vacuum at the club impressively for a 21-year-old. Malo Gusto (20) at fullback and Conor Gallagher (24) in the midfield also look like they have quickly adapted to their more leading roles. These players could quickly reach great heights and begin providing the developmental structure key in bringing the rest of the Chelsea portfolio to their full potential. A core of exceptional young talents could rapidly develop at Chelsea, and the Blues would have a roster to compete at the top level of Europe and the Premier League for a long time, along with a portfolio of players surplus to competitive requirements that the club can sell on for profit.

Chelsea fans won’t be thrilled about the comparison, but this good scenario could play out like a more aggressive version of the rebuild Arsenal initiated under Mikel Arteta. While Arteta’s early Arsenal teams had some veteran contributors like Granit Xhaka, Alexandre Lacazette, and even Gabriel Jesus, the team as a whole were relatively young and, early on, underperformed their price tags. But as prospects like Bukayo Saka and Martin Ødegaard developed, they began to provide a very high-level baseline of performance that other high-potential players like Gabriel Martinelli, Ben White, and others began to coalesce around. Arsenal are now one of the best teams in Europe, and because of how young they are, they can stay that way for a long time.

The bad outcome at Chelsea is essentially a failure to launch. Not enough players like Palmer develop early enough to provide a core in what turned out to be a sub-optimal developmental environment at Chelsea. The result is a London-based rendition of Lord of the Flies, with youth attempting to govern themselves but ultimately bringing out the worst in each other. The long contracts that initially allowed Chelsea to craft their portfolio now shackle them to severely depreciated assets, who, instead of developing together, are stunting each other's growth.

What’s scary about the gamble Boehly and Clearlake are taking at Chelsea is that failing looks a lot like what is taking place right now: a group of prospects who haven’t quite put it together and, therefore, aren’t currently competing and driving revenue. The question Chelsea will have to answer on the field going forward is whether enough of their youth investments can begin paying dividends, both in results and, perhaps more importantly, in the development of their fellow prospects. If not, Chelsea may be left waiting on the appreciation of their portfolio longer than they can afford.

Edited excellently by Greta Gruber

*UEFA and the Premier league, largely because of Chelsea’s recent business, have limited the length that clubs can amortize their players when trying to meet sustainability standards.

Great write up!