Choked Out: How Grapplers Took Over the UFC

On why strikers sell fights, grapplers win them, and the UFC wants you to watch Jiu-Jitsu

UFC 229 was Conor McGregor’s long-awaited return to the octagon. His lightweight title win two years prior had cemented his place in UFC lore, making him the first fighter ever to hold two belts. The publicity caused his fanbase to explode, and led to a celebrity boxing exhibition against Floyd Mayweather that moved McGregor from a notable UFC fighter to the stratosphere of sports celebrities.

McGregor’s opponent in his UFC homecoming was Khabib Nurmagomedov. Born in Dagestan, a republic of Russia, Khabib had risen undefeated to the title following McGregor’s UFC departure. While McGregor had won over legions of fans with his bombastic trash-talk and antics in the cage, Khabib was famously understated. Khabib made no court-side appearances at sporting events, featured in no commercials, and was without a signature whiskey like his Irish counterpart.

In addition to their temperaments, the two also differed in their fighting styles. McGregor had become the most dangerous striker in the UFC before his departure. Khabib, on the other hand, was the UFC’s best wrestler. In the lead-up to the McGregor fight, Khabib briefly stole the spotlight as a video surfaced of him wrestling a bear as a child in Russia.

At their five-round main event in Vegas, those styles clashed in a battle for the lightweight title. The fighters circled each other and exchanged punches early. Every shot landed by McGregor brought raucous cheers from the heavily Irish crowd. Khabib landed his first takedown a minute into the round, throwing McGregor to the ground and establishing a strong wrestling position. Khabib stayed there, slowly squeezing the life from McGregor, until the end of the first round four minutes later.

In his corner after the round, McGregor’s coaches urged him on. “That was [Khabib’s] best!” they told McGregor, imploring him to shake off the first round and keep the fight on the feet, where he could use his striking. The second round began, and after a right hook sent McGregor stumbling, Khabib again had McGregor’s back on the canvas, this time for four and a half minutes.

The decisive moment came in the fourth round. After Khabib had landed another takedown, McGregor had a momentary lapse in concentration. Khabib slid to McGregor’s back and locked his arms around the Irishman's neck. Khabib began to crank his arms, turning McGregor bright red before he eventually tapped, submitting.

Khabib’s dominance over McGregor shocked the UFC world. Yet as we look into the data, we find it’s also representative of a bigger trend. Grappling specialists like Khabib are consistently taking down big-name strikers like McGregor, and it’s changing the landscape of the UFC.

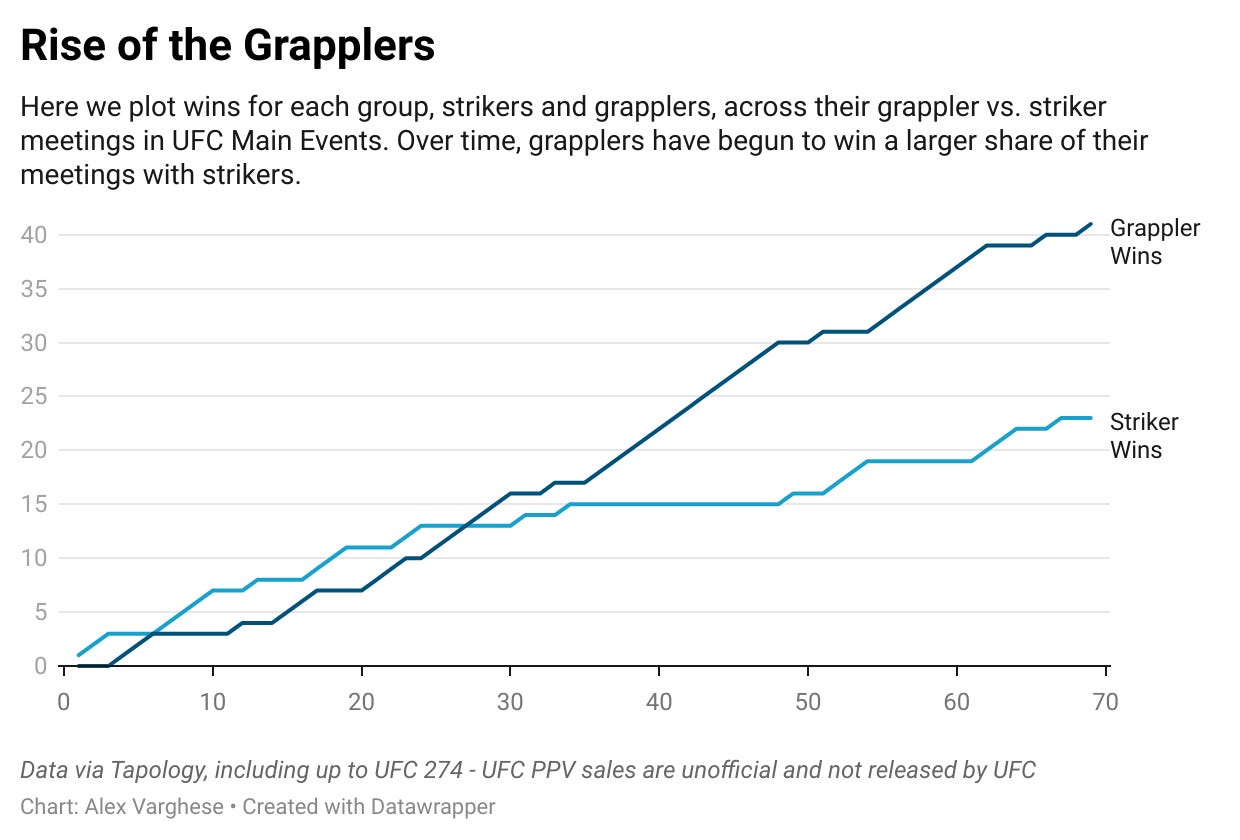

Rise of the Grapplers

Let’s begin by defining grappling. Grappling is a general term that captures wrestling and martial arts like Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo, and Sambo. While each style is different in origin and execution, they all employ a similar principle: control the opponent through takedowns and grips, and work through increasingly threatening positions to expose their weaknesses. In fighting, a grappling style is in contrast to a striking style, which encompasses boxing, kickboxing, and Muay Thai, and is generally more predicated on explosiveness and speed. Striking versus grappling is the battle of styles we saw between McGregor and Khabib: Power against control .

After witnessing Khabib’s total dominance over McGregor, with both of these fighters among the best at their respective styles, it poses the question: was the fight an anomaly, or does the grappler have a stylistic advantage over the striker?

To probe that question, we can look through past UFC fight data and see how grapplers did in fights against strikers. We assembled the data set by looking through the last 150 UFC pay-per-view main events, the 5-round fight that comes at the end of the night. Based on their primary style and background, we classified each fighter as a striker or a grappler.* While this may be a tad reductive, as some UFC fighters have more well-rounded styles that balance striking and grappling, this data set generally allows us to see who comes out on top when grapplers meet strikers.

The data is firmly in favor of the grapplers. In the last 150 UFC PPV main events, grapplers and strikers have met 50 times. Grapplers have won 34 of those meetings, compared to the strikers’ 15, with one draw. Moreover, over the last 15 meetings between strikers and grapplers, which stretches back to UFC 210 in 2017, grapplers have won 11 of the previous 15, suggesting that grappling is becoming even more favorable.

The question now is why grapplers seem to have a growing advantage in these big-time fights, and why is it seemingly more powerful today than before?

Why Grapplers beat Strikers

To understand why grapplers have an edge against strikers, let's look more deeply into one of the fastest-growing grappling styles in the UFC: Brazillian Jiu-Jitsu. Following its transplant to Brazil from Japan around 100 years ago, Jiu-Jitsu has grown a large following in the Americas over the last 20 years.

Brazillian Jiu Jitsu's first and foremost principle is to take the opponent off his feet and to the ground. To explain why, read this quote from world-renowned BJJ coach John Danaher on how the first phase of Jiu-Jitsu was derived: “When you put someone on the ground, dynamic, explosive movement is massively curtailed. It takes away the single riskiest element of fighting, which is quick dynamic movement that can generate kinetic energy. (...) It is inherently safer, less things can go catastrophically wrong on the ground than in the standing position.”

Here Danaher is talking about how Jiu-Jitsu evolved as self-defense in street fighting. However, it’s not hard to see how we can apply this idea to Mixed Martial Arts. When a grappler takes his opponent to the ground, he takes away the opponent's explosive kicks and punches that they can generate on the feet, making knockouts much less likely. Think about it in terms of our Khabib versus McGregor example. McGregor was one of the most dangerous strikers in the UFC, but once Khabib took him to the ground, suddenly McGregor was striking from a position of much less leverage. Unable to generate the power in his shots that made him a two-division champ, the Irishman was not nearly as dangerous.

A common expression in sports is the “puncher’s chance.” The term's origin is in boxing and refers to how even the most overmatched fighter can win a fight by delivering a surprise knockout. What’s fascinating about grapplers coming up against strikers is that it takes away this puncher's chance. Less room for surprises leaves less room for upsets and a higher likelihood that grapplers grind out a win through more technical fights. How have fighters like Jon Jones and Khabib been able to go their entire careers undefeated? They never get surprised by a knockout. These fighters are superior grapplers, so they take the fight to the ground, where the chance of getting upset by a challenger becomes slim to none.

Grapplers have an edge in the UFC because they take away the striker’s biggest weapon: their power. While that leads to dominance for grapplers in the UFC, it poses an issue for the promotion: Do fans want to watch fights unlikely to have knockouts?

Strikers Sell

The UFC’s problem here is simple: Grapplers win big fights, but knockouts, and the strikers that deliver them, sell big fights.

Before we analyze that, a word on how the UFC makes money. The UFC works off a pay-per-view system, where viewers pay a flat fee ($80) to watch a five-fight card. There are typically around 12 pay-per-view cards per year. Unlike other major sports that make money by selling TV rights and using an advertising model, the UFC sells every card directly to the consumer. While on the one hand, that allows them to profit more from big-name fights, it also hurts them when weaker cards fail to generate as many pay-per-view buys.

Those big-name fighters, however, are often striking specialists. To illustrate that point, we can look back at our Main Event data, but this time analyze how often strikers and grapplers appeared in top pay-per-views as measured by sales. First, we can establish a baseline using the 100 best-selling UFC Main Events. Grapplers represent 44% of fighters in Main Event fights. That proportion shows us that grapplers appear in nearly as many main events as strikers. Does that parity persist as we get to higher selling fights?

When we look at the most successful UFC cards in history, those selling over 1M pay-per-views, grapplers fall to 34% of fighters, a 22% decrease from their representation in the top 100. When we zoom into the UFC’s biggest fights, the top 10 by sales, these fights feature only four grapplers, making up just 20% of fighters. Our data paints us a clear picture. UFC fans are less likely to buy fights featuring grapplers. The big sellers are those showcasing strikers.

When we think about the kind of action fans want to see in the octagon, we see the narrative playing out in the data. When Danaher talked about the grappler needing to bring their opponent to the ground, he reasoned that it reduced the chance of big strikes from the opponent. While that favors more technical fighters, it also reduces the big shots and knockouts that UFC fans are most interested in seeing.

A promotion where less marketable grapplers dominate more marketable strikers creates a clear problem for the UFC. As fighters continue to exploit superior grappling, there will be more top grapplers leading to more grappling-heavy fighting in Main Events, which we’ve shown to be less attractive to pay-per-view buyers.

How the UFC Responds

As grapplers have become increasingly successful in the UFC, it’s begun to force changes across the promotion both inside and outside the ring.

On the competition side, strikers have begun to add to their skillset to better deal with high-level grappling. “Anti-Wrestling” is an emerging tool utilized by top strikers to keep fights on the feet where they hold the advantage. Some of the UFC's best strikers, like Israel Adesanya and Leon Edwards, have risen to the top of their divisions by becoming experts in “takedown defense,” or the ability to prevent wrestlers from bringing them to the ground.

On the business side, the UFC has also been working to adjust to a grappling-heavy reality. In May 2023, the UFC announced the Fight Pass Invitational 4, a Brazillian Jiu-Jitsu tournament. On the surface, the card feels like a strange move by the promotion. The UFC holds no other non-MMA events under the “UFC” name, and we’ve established that it's striking that sells in the UFC, so why stage a grappling-only event? One reason may be to introduce high-level grappling to a more general audience and cultivate an appreciation for it amongst the UFC’s fans.

The Fight Pass Invitational features a matchup between Felipe Pena and Craig Jones, two of the best-known BJJ fighters on the planet. Behind them are former MMA fighters Glover Teixeira and Anthony Smith, familiar faces for the UFC community. Throw in a $25,000 single-elimination tournament in the style of the early days of the UFC, and the promotion has put together a grappling event to appeal to the UFC fan.

It would be no surprise to see the UFC stage more events like the Fight Pass Invitational to make grappling a more appealing prospect for their fans. As the fan base becomes more attuned to grappling, the UFC’s incentives become more aligned, and they can start putting the most successful fighters in the biggest fights while still cashing in on huge pay-per-view sales. Will the UFC be able to change the preferences of their fans before grappling overruns the promotion? If so, they’ll need to move fast - the promotion’s grapplers have them in a chokehold.

Edited excellently by Greta Gruber and Ty Belflower

*The classification of each UFC fighter as either a striker or grappler factored in each fighter’s experience before joining the UFC, their number of submissions vs. knockouts in competition, and commentary on their styles from across the internet.