David Becomes Goliath: Why the Little Guys are Running the NFL

On the biases of NFL evaluators, the economics of player safety, and how the league made room for a new type of star.

In April 2015, Melvin Gordon was one of the hottest NFL prospects in the country. He had just capped off a historic career at the University of Wisconsin with a 32-touchdown, 2,740-yard season that saw him finish second in Heisman voting, the exclamation mark a 251-yard, three-touchdown performance in the Outback Bowl. Analysts showered him with comparisons to NFL greats like Adrian Peterson, and he was a lock to break the two-year drought of running backs in the first round.

The 6’1”, 215 lb. Gordon looked like an elite NFL running back. When asked to evaluate Gordon, NFL scout Chris Landry said Gordon had “...so many of the qualities of Jamaal Charles, who right now is one of the elite backs, what we call blue-graded players. That’s the elite players in the league. (...) He’s got good size. He’s an absolutely violent jump-cutter. (...) I think anybody that wants to use a difference-maker is going to take this guy.” On draft day, the Chargers grabbed Gordon with the 15th overall pick and, by all accounts, had landed the star running back that would take their offense to the next level.

Two years later, Austin Ekeler began a much less buzzworthy pre-draft process. Ekeler had just finished his fourth season at Western Colorado, the only school to recruit the 5’8”, 195 lb. halfback. Despite the little attention he received out of high school, Ekeler lit up Division II, setting multiple school records and leading all DII running backs with a whopping 203 all-purpose yards per game.

On a chilly March afternoon in Colorado, Ekeler waited for the Division I players at the University of Colorado’s pro day to finish their drills so that he and 20 other Division II players could get their chance to work out in front of NFL scouts. This opportunity came with an added caveat: only the top three DII performers in the vertical and 40-yard dash would be allowed to continue their workout. The remaining players would be sent home, their NFL hopes dashed.

A third of the scouts in attendance had already headed for the exits by the time Ekeler readied himself for his vertical. He then posted a 40.5-in jump, higher than any running back at the 2017 Combine: ten inches higher than Dalvin Cook (30.5) and twelve inches higher than Leonard Fournette (28.5), two traditional, high-end running back prospects in the 2017 draft. Ekeler followed the vertical with a 4.48-second 40-yard dash, which featured a blazing 1.5s 10-yard split.

His performance earned Ekeler an NFL lifeline. Two years after selecting the much-hyped Gordon as the 15th overall pick, the Chargers signed the relatively unknown Ekeler as an undrafted free agent.

In 2017 and 2018, Ekeler served as an understudy to Gordon, picking up most of his production on passing downs in a “scat-back” role reserved across the league for undersized backs. Then in 2019, Gordon, seeking a market-setting contract, sat out the team’s first four games. Without another traditional running back on the roster, the Chargers turned to Ekeler to assume a three-down role. He responded, posting 490 yards and six touchdowns through week four. Gordon returned in week five, but not until after the Chargers saw what they had in Ekeler. The Chargers didn’t match Denver’s two-year, $16M offer to Gordon the following off-season and named Ekeler their new starting running back.

Fast forward to the 2023 season, and Ekeler is one of the top running backs in football. Gordon is a free agent after being cut in the 2022 season. It’s easy to chalk it up as just a classic underdog story: Ekeler, the under-hyped, hard-working back who kept at it until he got his shot; Gordon, the collegiate rock star who never quite lived up to his potential at the next level.

But what if the Gordon-Ekeler story pointed to a much more significant, league-wide shift in what constitutes a great prospect? It raises the question: What biases do NFL evaluators hold, where do they come from, and are they still good heuristics for predicting success in the modern game?

A Good Prospect vs. A Good Player

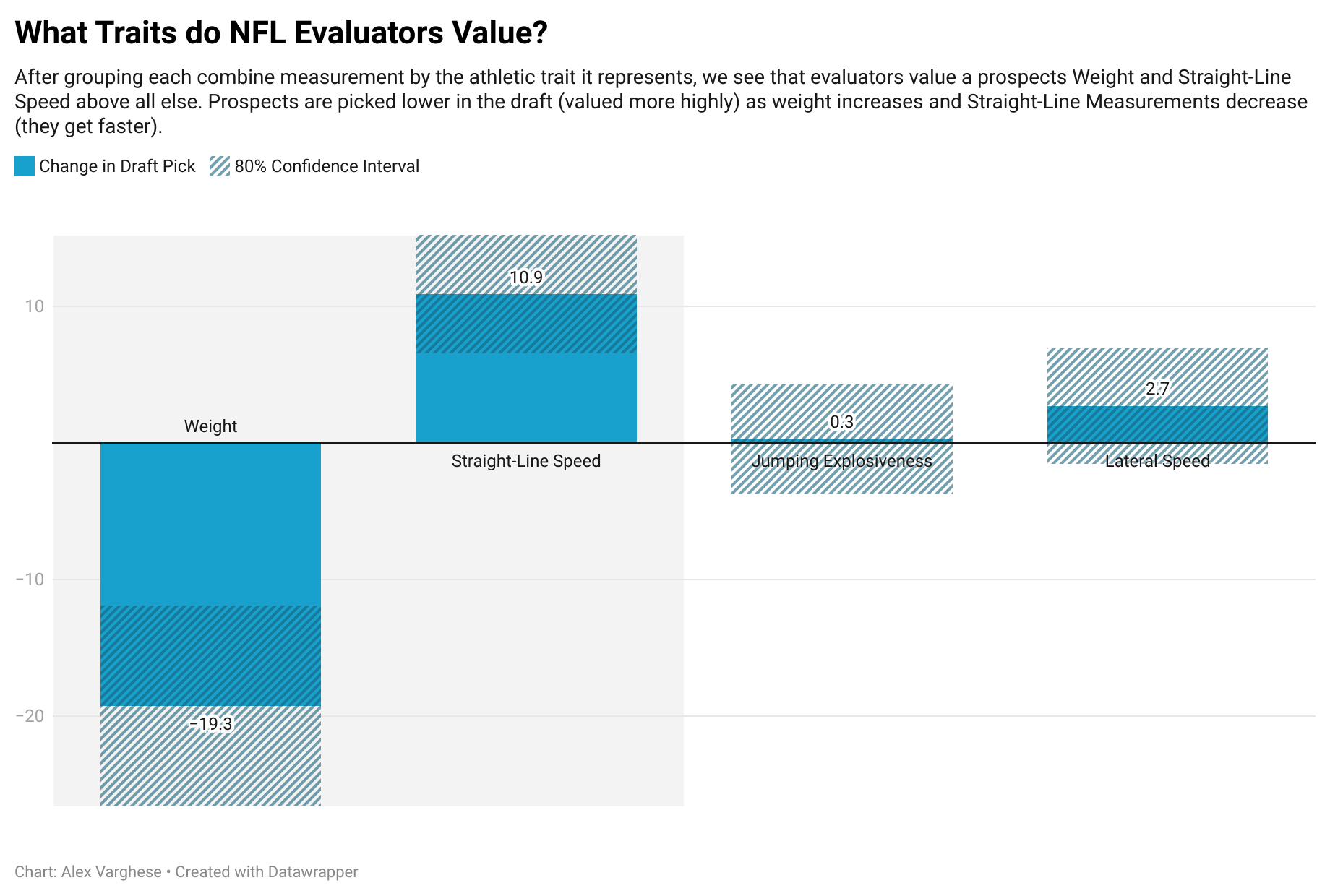

In identifying traits NFL evaluators (scouts or general managers) value in prospects, we have two metrics: NFL Combine scores and draft position. Combine scores help measure the physical characteristics of an NFL prospect. Each Combine drill captures a specific aspect of athleticism: the 40-yard dash and 10-yard split times align with straight-line speed and acceleration, broad and vertical jumps correlate with explosiveness, and the shuttle and three-cone drills measure agility and lateral speed. For the purpose of reducing multicollinearity, we’ll group combine metrics based on the athletic attribute they represent.

Draft position is a way to gauge a prospect’s perceived value. Teams pick highly rated prospects before lesser ones, so we get a direct measure of how each player is valued. In combining draft position with Combine scores, we have a way of understanding how each aspect of an athlete's composition might impact their value entering the league.

So what traits are the scouts looking for? Based on a multiple regression analysis, we see that scouts prefer running backs above average in weight and straight-line speed (measured by the 40-yard dash and 10-yard split). Even small changes in the measures associated with these traits can make a big difference on draft day: a one standard deviation increase in weight (11 lbs.) could buy a 20-spot jump on draft day. A one standard deviation improvement in the 40-yard dash (.1 seconds) or the 10-yard split (.05 seconds) was worth about ten spots.

An NFL evaluator’s archetype for running backs are players like Adrian Peterson, Jonathan Taylor, and Saquon Barkley. All are above average in weight, 10-yard split, and 40-yard times. All three are also examples of excellent running backs. What we need to answer, however, is if the size and speed of these stars are features that predict high NFL production in general and, therefore, would be good indicators to help evaluators pick players.

To understand which physical characteristics correlate with stellar NFL performance, we’ll use Football Outsider’s DYAR (Defense Adjusted Yards Above Replacement), explained in detail here. At its core, DYAR measures how many yards a player earns versus a “replacement level” player. “Replacement level” is a group representative of backup running backs. We quantify with DYAR: “How many yards does this player add to a team's offense compared to what a backup would add?” It’s also important to note that since DYAR is a cumulative statistic, durability factors into our performance measure (more missed games are fewer opportunities to accrue DYAR). That durability aspect of DYAR works for our analysis because while staying healthy isn’t a skill per se, it does increase a player’s value.

For the performance metric, we look at the amount of DYAR accumulated during each player’s rookie contract window. We’ll choose the rookie contract period for a couple of reasons. First, the 4-year sample size gives players enough time to find their feet in the league and their proper place on the depth chart. Often, even the most talented rookies will start as backups to more savvy veterans who know the intricacies of the offense. Second, the rookie contract window is brief enough that it doesn’t capture past most players' age 28 seasons, where data has shown some running backs begin to regress.

Armed with our DYAR performance metric, we can run another regression using our Combine variables as predictors to see what physical traits align with production in the NFL.

These results are where things get more interesting. Although evaluators are correct in believing speed correlates to high performance, weight, which significantly influenced draft position, has almost no correlation to the output of NFL backs. This relationship means that over the years, bigger NFL players have been drafted earlier, despite producing no more than lighter backs.

Note that the sample for our results above is running backs who played in the league between 2007 and 2020. However, we may be able to generalize our findings beyond just running backs. In an analysis looking at the weight of the league’s top wide receivers, the authors found that lighter wide receivers were steadily making up a larger proportion of top performers since 2010.

It’s also important to keep in mind that although we found a general trend in size not being an essential factor for skill-position players, there are notable exceptions. One that will be top of mind for most NFL-savvy readers is Derrick Henry. Coming in at 6’3”, 247 lbs., Henry has utilized his enormous frame to become the most feared running back in the league over the past few years. On the receiver side, players like DK Metcalf and AJ Brown also stand out as bigger receivers who gain an advantage from their imposing figures and physical style of play. What we should take away from the analysis, however, is that these players may be more of the exception than the rule.

Evaluation Dissonance

We’ve now established that NFL evaluators put a premium on size when it doesn’t correlate with success. Why is this the case?

The answer may lie in the tradition of NFL player evaluation and a disconnect between the modern NFL and the assumptions of scouts and GMs. NFL offenses have evolved continuously throughout the game's history, mainly alongside changes in the rule book. From the 1905 rule changes sponsored by Teddy Roosevelt that spawned the first forward pass, to 1933, when passing was allowed anywhere behind the line of scrimmage, to the more recent changes that emphasize freedom of movement by receivers and player safety, the NFL rulebook has always evolved to improve its product and protect its players.

Along with these rule changes, there has been a rise in offensive production. The recent player movement changes (essentially restricting how much defenders can contact pass catchers) have influenced the league's shift to more pass-centric, high-flying offenses. It makes sense: as the defense can contact receivers less, it is easier for them to get open and for quarterbacks to throw the football to them.

The NFL is also protecting offensive players from bigger, injury-causing hits. In 2002, the NFL outlawed helmet-to-helmet hits against quarterbacks. In the mid-2000s, the league banned blind-side blocks and emphasized officiating on the cut block. In 2011, the NFL added receivers to the “defenseless players” list, protecting them from violent collisions. As we approach the 2023 season, it is illegal to launch into a quarterback, land on him with your body weight, and hit him high (shoulders or above) or low (knees or below).

Why has the league made these changes to the rules? The obvious answer is player safety. The more cynical, yet perhaps correct answer, is to protect its product.

According to Nielsen, the NFL accounted for 82 of the 100 most-watched telecasts last year, the highest proportion on record. After adding a $14 billion deal with YouTube TV, the NFL’s domestic media rights are worth over $120 billion. The Denver Broncos were purchased this past year for $4.6 billion, and the Washington Commanders are on the verge of selling for an NFL record $6 billion, an indicator of the rising value of NFL franchises and projected viewership growth.

The NFL is a business fueled by stars. The league understands very well that its multi-billion dollar machine requires its best players to be healthy and to play week after week. Using their most potent lever, the rulebook, the NFL has worked to reduce injuries in its star players to ensure you can tune in to watch them each week. The unexpected outcome is a new archetype of skill-position players. With the rulebook now protecting players from violent, injury-causing hits, a crop of smaller, faster, more skilled players has found a foothold in the league.

This phenomenon is unfolding across NFL offenses. Think of running backs like Alvin Kamara, Aaron Jones, and Christian McCaffrey, who have put up historically large numbers while undersized. On the receiver side, we can quickly point to Jaylen Waddle, Tyreek Hill, and DeVonta Smith, all three of whom are in the top eight for wide receiver DYAR and at least 10 pounds under the average NFL wide receiver weight.

DeVonta Smith, in particular, is a very intriguing case. Smith won the Heisman in his final year at Alabama, posting over 1,800 yards and 23 touchdowns. At 6’0, 165 lbs., Smith has the slightest frame of any WR in the league. Concerns about his size and ability to hold up against NFL defensive players riddled his pre-draft process with uncertainty. The Eagles took a chance on his talent, hoping he would prove wrong those who thought he was too small to be a top receiver in the league. Smith responded by posting 2,112 yards and 12 TDs over his first two years. He has not missed a single game in his first two seasons. He is also proof of the NFL’s new capacity for undersized stars.

NFL football has always been a game defined by violence. NFL players are some of the most explosive athletes on the planet, launching themselves at each other with almost unimaginable force. It makes sense that larger players would be more likely to sustain that force, produce it, and get up again. Consequently, preferring bigger players to smaller ones has been the modus operandi for NFL evaluators for a long time. At the top of a 1997 blog post by coaching legend Bill Walsh about evaluating the running back position, it simply reads, “Ideal size: Large enough to take punishment.”

The NFL has reduced that punishment. The reasoning was to protect the stars that keep you buying tickets and glued to your television screen. At the same time, they also made room for a new type of star that trades yesterday's brute force, freight-train style for a slighter, more skillful one that suits the modern game. As the league comes to grips with a prospect’s size decreasing in importance, we would expect that more NFL players will resemble the latter than the former.

Perhaps now we can make sense of what happened with Ekeler and Gordon. Evaluators saw in Gordon precisely what they had been looking for: a big, traditional back, ready for a three-down role. They saw in Ekeler the kind of prospect you stay away from: a back too small to take the league's punishment. What they did not see was the ground shifting beneath them as they were evaluating. Every time the league updated the rule book, their preference for the big guy got further from a helpful heuristic and closer to a hurtful bias. It led to 31 teams passing on Ekeler, who has been one of the best backs in the league since the Chargers gave him a shot in 2017.

Are there any more Ekeler-Gordon cases lurking across the league? We saw Tony Pollard supplant Ezekiel Elliott in Dallas and turn into a bona fide star last season after years of being seen as a change-of-pace option. In this year’s draft, Mike McDaniel, whose Dolphins team utilizes smaller, quicker players better than almost anyone in the league, picked up running back Devon Achane, who boasts a lightning-quick 4.32s 40-yd time at 5’8”, 188 lbs. He comes into the league with concerns that his small frame won’t be able to handle a large workload. Only time will tell on Achane, but he can take comfort in knowing there is plenty of room for the undersized star in today’s NFL.

Edited excellently by Greta Gruber

Enjoyed this piece? Subscribe below to get more content from me in the future delivered to your inbox. It’s free and your support means a lot.