Like Mike: Comparing The Clark Effect to the Jordan Effect

On calculating the Clark effect, how it could rival the Jordan effect, and why it'll change the league for good.

It was the early 1980s, and America was not watching the NBA. Most stadiums were half empty at tip-off, and the league’s TV deal with CBS was worth $18.5M a year - less than many teams pay their sixth man today. Fewer than half of the league’s 23 franchises turned a profit.

The NBA owes its huge turnaround - from the scruffy upstart of its early years to the $120B behemoth it is today - to several characters. Magic Johnson and Larry Bird arrived from the college ranks to give the league a story worth watching. David Stern became commissioner in 1984, passed a landmark Collective Bargaining Agreement, and began shaping the NBA into a global brand. But more than any of these factors, and perhaps even more than all of them combined, Michael Jordan made the modern NBA.

In Jordan’s rookie year, the NBA’s 23 teams had a combined revenue of $165M. When Jordan retired from the Bulls in ‘98, league revenues had grown to $2.75B. They called it the Jordan effect. In 1998, Fortune magazine, leaning heavily on a study by economist Jerry Hauser1, calculated that Jordan on his own generated $3.6B for the NBA by his second retirement. Jordan sold out every game, home or away. Broadcasting deals multiplied as networks desperately tried to get Jordan on their station. League merchandising revenue grew to $3B in the 1990s, and one in every four purchases was a Michael Jordan jersey.

If this sounds familiar - a basketball player whipping the country into a frenzy and transforming their league - it’s because we’re seeing it again today: They’re calling it the Clark effect.

Feeling the Clark Effect

You have seen what Caitlin Clark does on the basketball court - everyone has - and that’s the point. She’s a walking highlight reel of 40-foot three-pointers and behind-the-back passes, delivered with a vicious competitiveness and unbridled joy that manifests into a Jordan-like charisma - and inspires Jordan levels of fandom.

In her last season at Iowa, Clark’s Hawkeyes broke the record for the most watched women’s college basketball game three times. When the ratings for the women’s Final Four dwarfed that of the men’s tournament, it became clear that Clark wasn’t just the biggest draw for women’s college hoops, but simply one of the world’s biggest draws.

Clark was drafted first overall by the WNBA’s Indiana Fever, and the Clark effect has already begun working on the women’s pro game. The get-in price for Clark’s WNBA debut is $130 - around three times the average ticket price for a WNBA game. The Las Vegas Aces, L.A. Sparks, and Washington Mystics have moved their games against the Fever into bigger venues to accommodate the massive demand. For the first time, three WNBA teams have sold out their season tickets, and owners are attributing the sales to the Clark effect.

The record-breaking ticket prices driven by the Clark effect have also made the news in a less celebratory light, as analysts compared them to the $75k Clark earns annually on her rookie contract. Clark’s salary is much lower than that of men’s basketball players because it’s capped relative to the WNBA’s league-wide revenues, which last year were around $200M. Even with strong recent growth, that $200M is less than many NBA franchises make on their own.

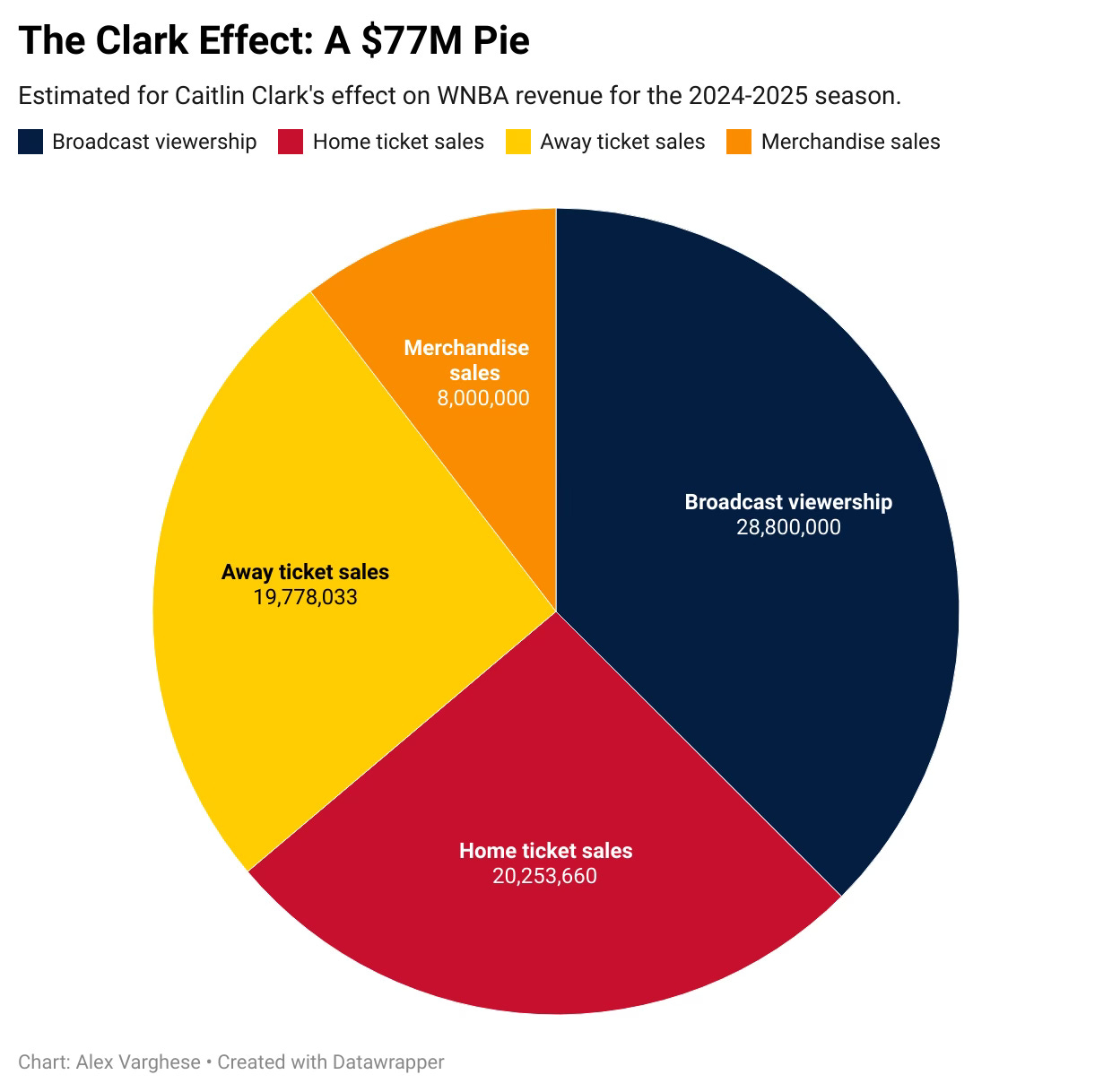

It’s a given that Clark will increase that league-wide revenue this season - but by how much? I applied the framework that Hauser and Fortune used to calculate the Jordan effect, plus some Fermi-style estimation2, to determine what the Clark effect on the WNBA might look like this season.

Calculating the Clark Effect

The four biggest ways Clark can drive WNBA revenues are by increasing:

Away game ticket sales

Home game ticket sales

Broadcast viewership

Merchandise sales

Let’s start with Clark’s effect on away ticket sales. Last year, the average ticket for a WNBA game was $47, and the average attendance was 6,615 people per game. The average WNBA stadium seats 13,078 people, which is important because Clark is selling out her road games. SeatGeek reports that the average resale price for an away Fever game is around $200. We’ll multiply the additional 6,463 tickets Clark is selling to fill the arena at an average price of $200 while adding a $153 premium to the 6,615 tickets that were already selling. That calculation has Clark adding around $2,304,761 in revenue each road game. WNBA teams have been selling their Fever tickets at higher prices or bundled with other tickets to capture this additional value, but let’s assume that half of the revenue goes to the resale market and doesn’t get back to franchises, putting the Clark revenue for road games at $1,152,380. Multiply that across her 20 away games, and that comes to $23,047,616 in additional revenue for the league.

Clark also plays 20 home games. The Fever play in a 17,923-seat stadium but only averaged 4,067 attendees at their games last year. Clark and the Fever sold 13,000 tickets for their pre-season home opener against Atlanta. We’ll estimate the team sells around 13,000 tickets for regular season games as well, assuming the pre-season factor and Clark home debut factors are off-setting. Eye-balling Ticketmaster, the average ticket price for home games is around $100. Assuming Clark sells 8,933 additional tickets at the average price of $100, and the 4,067 tickets being sold before are $53 more expensive than average, that is good for an additional $1,108,851 per game. Because the Fever have sold many of these seats as season tickets or in bundles, they should get a slightly higher slice of the revenue than the away teams. Let’s assume they keep 75% of revenues, for $831,683 per game - that brings us to $16,632,765 across the 20 home games.

Next is broadcasting. The WNBA’s current package of TV deals nets them $60M annually, and each broadcast averages 505,000 viewers. Last season, NCAA women’s college basketball viewership was up 60%. Let’s assign Clark 80% of the credit, giving other stars like Paige Bueckers, Kamilla Cardoso, and Angel Reese their due as well. Assuming Clark contributes similar interest to WNBA games, that would add roughly 240,000 viewers to an average broadcast (and Clark is on a lot of the broadcasts). The WNBA will get a chance to renegotiate its TV deals in 2025, and they were already likely to significantly increase the price of their rights package, with commissioner Cathy Engelbert saying she wants to “at least double” TV revenues. Assuming broadcast partners value each additional viewer at the current $120 per average viewer per game, that would make viewers added by Clark worth a collective $28.8M this season.

Lastly, the WNBA store is selling a lot of Caitlin Clark merchandise, but the league hasn't disclosed how much. When measuring Jordan’s NBA apparel effect, the Fortune authors noted that apparel was 1/5th of the league’s total revenue. For the WNBA, that would be $40M, based on last year's numbers. Jordan was estimated to drive 20% of the NBA’s merchandise revenue, and although Clark’s share of WNBA merchandise is probably much higher, we’ll stick conservatively with 20%. That is an additional $8M in revenue.

Summed across all four categories, Clark yields an estimated $76,480,381 in incremental revenue - more than a third of what the entire WNBA made last season. That prediction comes with a lot of uncertainty, but even if we gave a conservative $20M margin for error to account for it, the effect remains the same: Clark is going to make the league paradigm-shifting revenue this season.

When we adjust Hauser’s estimation of the Jordan effect in '91-’92 for inflation, it comes to $113M. As huge as the Clark effect might seem, suggesting that as a rookie, she could generate 70% of the revenues Michael Jordan did in his prime seems heretical. And our estimate could be high: more of the money could end up in the resale market than anticipated, society could begin to feel some Clark fatigue, or injuries could cool off viewership.

However, considering how the world has changed since Jordan left the NBA, I think it’s also possible the Clark effect could, in the long run, create more league revenue than the Jordan effect. Jordan is as big a star as we’ve ever had in sports, but he dominated in a much less connected world. The internet and the smartphone were not widely adopted until after his time with the Bulls. There weren’t opportunities for the NBA to showcase, and ultimately monetize, Jordan on YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok. If you wanted to see him, you either tuned in for the Bulls game or bought a ticket.

The Clark effect is taking place in a world built for virality, and Clark’s game is a perfect fit for it. The deep threes and flashy passes are built to be packaged into 15-second clips for you to consume and then share on your smartphone. In the age of the influencer economy, Clark’s greatness has earned her more influence than nearly any person on the planet, and it pays - not just for the league today, but perhaps for generations.

Widening The Base

When Jordan entered the NBA in 1984, the owners and players started to benefit immediately, but perhaps a more lasting legacy is how the Jordan effect drove more star players to the NBA. There’s an inspirational aspect - LeBron and Kobe glued to their TVs, wanting to be “like Mike” - but consider the more concrete changes that Jordan enabled to improve the NBA’s talent pool, and how that talent pool has driven the league’s growth long after Jordan retired.

The average salary in Jordan’s rookie year was $286,0003. Today, NBA players are the highest-paid athletes in American sports, with an average salary of $9.7M. When Jordan left the league, six more cities had an NBA team, bringing the game to new markets. Before Jordan, CBS played the Finals on tape delay at 11:30pm after the local news, but by the time he left, even regular-season NBA games had a prominent position on network TV. Jordan’s celebrity helped drive David Stern’s vision to make the NBA an international product, and last season (23-24), four out of five All-NBA first-teamers were international players: Nikola Jokić, Giannis Antetokounmpo, Luka Dončić, and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander.

The changes driven by Jordan have seen the league create more stars and generate more revenue. Using

‘s Raptor metric4 to approximate the number of stars in the league (I labeled stars as players who played 30 games and 1000 minutes with an eRaptor > 4), we see a steady increase from the pre-Jordan era to today - up to 19 stars in 2024 from 9 in 1983. This constellation of stars, made possible by the Jordan-effect, now spurs the growth of the NBA through their own LeBron effects, Giannis effects, or Curry effects, and provides the widening base for the NBA’s exponential growth.

We’re already seeing the WNBA benefit from the Clark Effect. The league announced that for the first time, all flights would be chartered this season. Reigning MVP A’ja Wilson just got her own signature sneaker from Nike, no doubt helped by the increased attention on the league. But while these immediate gains are huge for the WNBA, the long-term Clark effect could be even larger. How many female athletes will consider becoming a WNBA player once Clark effect revenues raise the average salary from $113,000? How many more expansion franchises will pop up, made economically viable by a Clark effect WNBA? How many international fans and future players will Clark win the league when, just like Jordan and the Dream Team in 1992, she (presumably) heads to the Olympics this summer with Team USA? The opportunity Clark has given the WNBA to discover new markets, and new talent, could change the league for good.

Not bad for $75k a year.

Edited Excellently by Greta Gruber

Ironically, Jerry Hauser is a Clark medalist, which is like the MVP award for economics.

The technique is named after Enrico Fermi, who you might have seen depicted as part of the Manhattan Project in Oppenheimer. Fermi estimation is breaking a problem with many unknowns into small pieces you estimate separately and combine. The technique works because you’re equally likely to under or over-estimate any one part of the problem. This means when you combine many aspects, those over and under-estimations should cancel, leaving you closer to the answer than just guessing off one parameter. Check out this link for more.

$286,000 doesn’t sound that bad, but considering the level of skill required to play in the league, and the short career of the average NBA player, it wasn’t that great of a deal.

I chose 4 by looking for a round number in 2024 where I felt the stars ended. The last player in this season is Derrick White, who may not scream star, but just above him is Jayson Tatum, who does. The last player in for 1983 was Gus Williams.

This is an all-timer for you, Alex 😳

favorite piece so far!