Limits: How the MLB Can Save its Pitchers

Verlander and Scherzer's "qualified start" can fix the league's injury problem, and perhaps its product too.

A baseball thrown at 100mph shows us our limits.

It travels the 60 feet from mound to plate in 400 milliseconds, the same amount of time it takes to blink. On the front end of that 400 ms, the hitter's nervous system takes 100 ms to process that the ball is being thrown. On the back end, it takes 150 ms to swing the bat. What is left is 150 ms in the middle for the hitter to decide if they should swing, and if so, where. Here is where the limits lie: the human eye cannot continuously track the ball moving towards it at 100mph. The hitter sees flashes of white as if through a shutter on a camera, leaving him flapping at thin air or, if he’s more honest, standing frozen in defeat1.

The fastball is baseball's best pitch, and the faster, the better. As pitch speed increases, batting averages and quality of contact decrease, leading to quicker outs and fewer runs. As the MLB's analytics era made it clear that velocity is pitching gold, it has led to a fastball arms race (pun intended). In 2008, there were 147 pitches thrown 100 mph or faster. In 2022, that number had reached 3,356. In that same year, batting averages fell to .243, the lowest number since 1968.

But as pitchers throw faster and 98, 99, and even 100 mph pitches have become more common, we’ve seen that the hitter's eye wasn’t the only natural limit being tested.

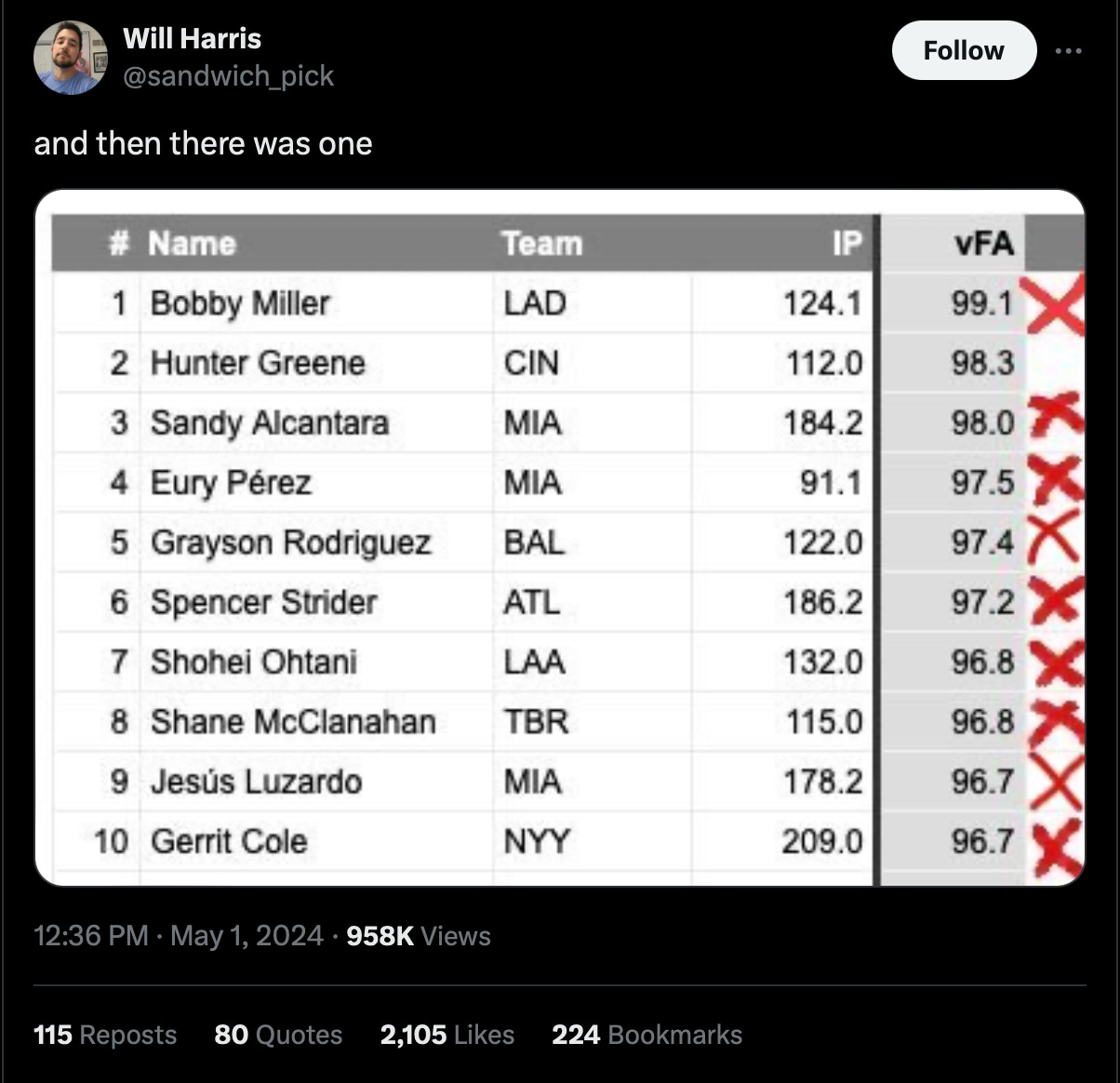

This is a tweet from

, who writes , that shows the pitchers with the top-10 average fastball velocities in 2023. The ominous red Xs indicate that 9 out of 10 have been on the injured list this season with arm issues. It is a jarring piece of evidence for a problem that is verging on existential: The harder pitching so coveted in today’s MLB is destroying its pitchers.The UCL, or Ulnar Collateral Ligament, is a 5 mm strip of tissue around the elbow responsible for stabilizing the arm during the throw. As the pitcher has improved the efficiency of the shoulders and hips to increase torque, he has begun to deliver so much force to the UCL that, pitch by pitch, it frays like an overworked chord of rope. Eventually, this leads to a full rupture of the ligament and lands the pitcher on the operating table for the infamous Tommy John surgery. Along with it comes an 12-18 month layoff and no guarantee that arm is ever quite the same. For amateur players, the odds of making the MLB after Tommy John surgery is cut in half.

UCL injuries have increased alongside fastball velocity. Teams have tried to stem the tide of these injuries by pulling pitchers earlier and rotating more heavily through the bullpen, but the problem is that it isn’t volume alone causing UCL injuries. Researchers have found that the greatest predictor of injury is the frequency of “max-effort” pitches, those throws approaching three digits on the radar gun. One study estimates that every 1% increase in the proportion of max-effort fastballs results in a 2% increase in the likelihood of a UCL injury.

Today, a pitcher's performance is directly at odds with his longevity. His optimal strategy, and the one he will be rewarded an MLB contract for, is to throw many max-effort pitches, knowing that each one likely tears away a small piece of his UCL. Expose the limits of the eye, and face the limits of the elbow.

Two of baseball’s best-known pitchers, however, have offered a solution: If the best way to throw in today’s game is bad for pitchers, then change the game.

The Qualified Start

Asked about the rash of pitching injuries early in the 2024 season, Justin Verlander offered a solution called the “qualified start,” masterminded by fellow future Hall-of-Famer Max Scherzer.

The qualified start proposes that teams who stick with their starting pitcher through one of three minimums (Verlander only mentions a 90-pitch minimum in the video above, but Scherzer has included six innings or three runs allowed in his plans to add flexibility) are free to use their designated hitter for the rest of the game. If teams substitute their starter before hitting one of the minimums, they’ll lose access to the DH, and their pitcher will have to bat in that spot instead. Preserving the DH in the batting lineup instead of the pitcher is a powerful incentive. Pitchers hit at a .174 BA with a Slugging percentage (SLG) of .221, compared to a .262 BA and .442 SLG for designated hitters. In other words, access to the DH is worth a lot of runs.

This creates an incentive for teams to change their pitching philosophy from short, high-intensity outings to longer, lower-intensity ones. For pitchers to hit the 90-pitch threshold, they’ll need to essentially pace themselves, relying less on demanding high-velocity fastballs and more on placement and “old-school” tactics like throwing to weak contact. Pitchers would throw more pitches, but fewer of the max-effort pitches that are most likely to damage the UCL, potentially leading to fewer injuries.

The qualified start could also reduce injuries in the MLB pipeline. UCL injuries aren’t just on the rise in the majors, but also in the minors and college. Celebrity surgeon Dr. James Andrews reports that youth and amateur players went from accounting for 12% of his Tommy John surgeries in 1998 to 33% today. These injuries to young pitchers are the result of them following their upstream incentives: Young players accumulate higher volumes of max-effort pitches as they chase the high-velocity fastball, a modern pre-requisite for an MLB contract. In the video above, Verlander argues that as the qualified start creates a healthier optimal style for MLB pitchers, amateurs striving for those starting jobs will adapt their own styles to match.

“The trickle down permeates to Little League Baseball. Everyone is trying to get to this level. You want to throw D1? You’ve gotta throw hard and spin the ball well. Want to make the Minor Leagues? You’ve gotta throw hard and spin the ball well. … The second that you begin incentivizing pitching [slower], and guys are getting drafted because they can pitch and get guys out, then that goes down a level and then down a level. I just hope we don’t wait too long.”

Verlander’s fix aligns incentives for pitchers and their clubs, rewarding more strategic pitching, which promotes pitchers’ longevity. What makes his solution so elegant, however, is that altering optimal strategies for offenses and defenses may positively affect the game beyond saving starting pitchers.

The Three Outcome Problem

In the early 2000s, Baseball Prospectus writer Christina Kahrl began referring to the home run, strikeout, and walk as baseball’s “Three True Outcomes.” The phrase was used in analytics circles as a joke, implying that as baseball evolved, all at-bats would converge to one of the three outcomes - reducing the game to hit and catch.

Twenty years later, we live in a Three True Outcomes era of baseball. Strikeouts and home runs hit record highs in 2021 and have remained near those peaks since. Verlander claims the MLB’s shift towards this new equilibrium began in 2016, when the league started “juicing” the baseball to fly further, making it easier to hit home runs. Pitchers responded by altering their strategy to throw fewer hittable pitches, accelerating their shift towards max-effort pitches and throwing further toward the edges of the zone, leading to more walks and strikeouts. In turn, the drop in hittable pitches made it more difficult for hitters to string together multiple base hits in an inning, so hitters began going for broke, swinging big for home runs more often. Each side has continued to escalate their strategy, throwing harder and swinging harder, on their way to the modern three outcomes reality.

Over this recent stretch of rapidly increasing home runs and strikeouts, baseball’s popularity has sharply declined, with the all-star game and World Series drawing a fraction of the viewers they did in the 90s and 2000s. The change in gameplay certainly hasn’t helped. As baseball fulfills the Three True Outcomes prophecy, what has decreased are the balls actually put in play. Base hits are down, and with it, running and fielding - what some people call the “action” in baseball. “Action” is an apt description because without these plays, baseball alternates between a game of catch and a round of golf, neither of which draw great Nielsen ratings.

Baseball has a lot of problems that have contributed to its decline, including an aging fanbase, a lack of star power, and the NFL and NBA stealing viewers. There is likely not one lever for the MLB to pull that will make the game America’s pastime again overnight. But as we look at the strategic evolution in baseball, it’s alarming that both offenses and defenses have discovered that optimal strategies for the current rules are to generate less action.

The qualified start changes the calculus for offenses and defenses, incentivizing more action-driven strategies. As pitchers playing to reach a 90-pitch threshold reduce their max-effort pitches, they’ll throw more hittable baseballs. As hitters begin to see hittable pitches again, their optimal strategy may shift from trying to smash them all to accumulating base hits. The equilibrium would likely settle in gameplay with more action and less of the three outcomes.

We’ve seen other major sports leagues tinker with the balance of their product recently to great effect. The NBA has also been converging to its own three outcomes over the past few years - three-pointers, layups, and free throws. As covered by

, the league made a refereeing change at mid-season directing referees to call fewer fouls. The directive shifted optimal strategies for offenses, which had converged towards manufacturing free throws. Even as the change reduced scoring - teams averaged 4 points-per-game fewer after the All-Star Game than before - many fans and pundits preferred it. Gone were the whistles that had permeated every offensive possession. The game flowed more easily and had more action as offenses abandoned their formulas for getting to the free-throw line in favor of an entertaining alternative: scoring in the run of play.The MLB’s recent gameplay changes have tended to treat the symptoms rather than the cause of baseball’s lower-action equilibrium. Increasing the base size, reducing defensive shifts, and even introducing the pitch clock are meant to encourage action but don’t address the fundamental problem: both the offense and defense are rewarded for putting fewer balls in play.

The qualified start changes that, promoting strategies that encourage hitters and pitchers to pursue more action. If the MLB decides to take it up, it could create a game with not only healthier pitchers, but perhaps one with more entertainment for a public clamoring for more than three outcomes.

Edited Excellently by Greta Gruber

All these numbers are from this excellent Seattle Times piece.

It’s fascinating seeing the push/pull between optimizing how the sport is played vs making the most watchable/entertaining sport. While the three true outcomes, the shift, flame-throwing pitchers may be the best way to play the game, it’s not the most entertaining (or sustainable as it appears). I’ve read a decent amount about game design in video games and applying those thoughts to a 100+ year old sport is always fun

Tanner Houck for Cy Young