Saviors: How to Find a Franchise Quarterback

On the quarterback-savior cycle, why teams can't beat the draft, and how front offices dominate the NFL with longer time horizons.

In the 1999 NFL draft, The Cleveland Browns selected quarterback Tim Couch with the #1 overall pick. Couch was the beginning of a new era in Cleveland. After the team suspended operations for three years amid a stadium controversy, the Browns were starting from scratch, and Couch was their centerpiece.

Couch looked like a slam-dunk prospect to lead the Browns. As one New York Times article said, “[Couch] stands out the way lobster distinguishes itself from a quarter-pounder. Nothing against the other passers available, but few of them can run an offense the way Couch does. Couch has something that is difficult to teach: an ability to feel a football game, a talent that many quarterbacks spend years trying to develop.”

But despite his pedigree, Couch struggled for his four seasons as the starter, ultimately failing to materialize into the Brown’s franchise quarterback. In the years that followed, so did Ty Detmer, Doug Pederson, Spergon Wynn, Kelly Holcomb, Jeff Garcia, Luke McCown, Trent Dilfer, Charlie Frye, Derek Anderson, Brady Quinn, Ken Dorsey, Bruce Gradkowski, Colt McCoy, Jake Delhomme, Seneca Wallace, Brandon Weeden, Thaddeus Lewis, Brian Hoyer, Jason Campbell, Johnny Manziel, Connor Shaw, Josh McCown, Austin Davis, Robert Griffin III, Cody Kessler, DeShone Kizer, Kevin Hogan, and Baker Mayfield.

The Browns moved on from Mayfield in 2022 with a blockbuster trade for Deshaun Watson. In the two seasons since, they’ve added eight more names to the list of quarterbacks to take the reigns in Cleveland as Watson served a suspension and worked through injury issues. The Browns have had 38 signal callers in the 24 seasons since they selected Couch, none worthy of the title “franchise quarterback.” Ask Browns fans about their luck at the position since they returned to the NFL, and you’re likely to get one word: cursed.

If you hop in your car at Browns stadium and take I-90 west to Chicago, then swing north, hugging the Lake Michigan shoreline on your right, you arrive in a city whose fortunes at the quarterback position couldn’t be more different than Cleveland’s. While the Browns have slogged through their 38-quarterback procession, The Green Bay Packers have had a succession of three franchise quarterbacks, starting in 1992: Brett Favre, Aaron Rodgers, and Jordan Love1.

The difference in production and continuity at the quarterback position has manifested in the win column for both Cleveland and Green Bay. Since the Browns returned to the NFL in 1999, they have had the fewest regular-season wins of any NFL franchise (136), while the Packers have the third most (248).

Look at the run of quarterbacks in Green Bay and Cleveland, and on the surface, we see a story about how picking the right quarterbacks is essential to success. Look deeper, however, and the difference between Green Bay and Cleveland might not be the quarterbacks they choose but the chances they give them to succeed.

The Savior Cycle

In the 2024 NFL draft later this month, ESPN’s Mel Kiper projects that five quarterbacks will go in the first twelve picks: Caleb Williams, Jayden Daniels, Drake Maye, J.J. McCarthy, and Bo Nix.

This heavy concentration of quarterbacks going to the losingest teams at the top of the draft is business as usual in the NFL. Good quarterbacks are the most important ingredient to winning. In their piece on using WAR (Wins Above Replacement) in football,

and his colleagues estimate that quarterbacks are roughly five times more valuable than the next most valuable position.Because of their outsized value to winning, quarterbacks drive a cycle that sweeps up nearly every NFL team. Teams without a solid option at quarterback often lose themselves into a top draft choice. Those top draft choices feature elite quarterback prospects, the highest quality options at the position that drives the most wins. If that quarterback does turn out to be the franchise savior, then the team become contenders and vacate the top draft picks for the next quarterback-needy teams.

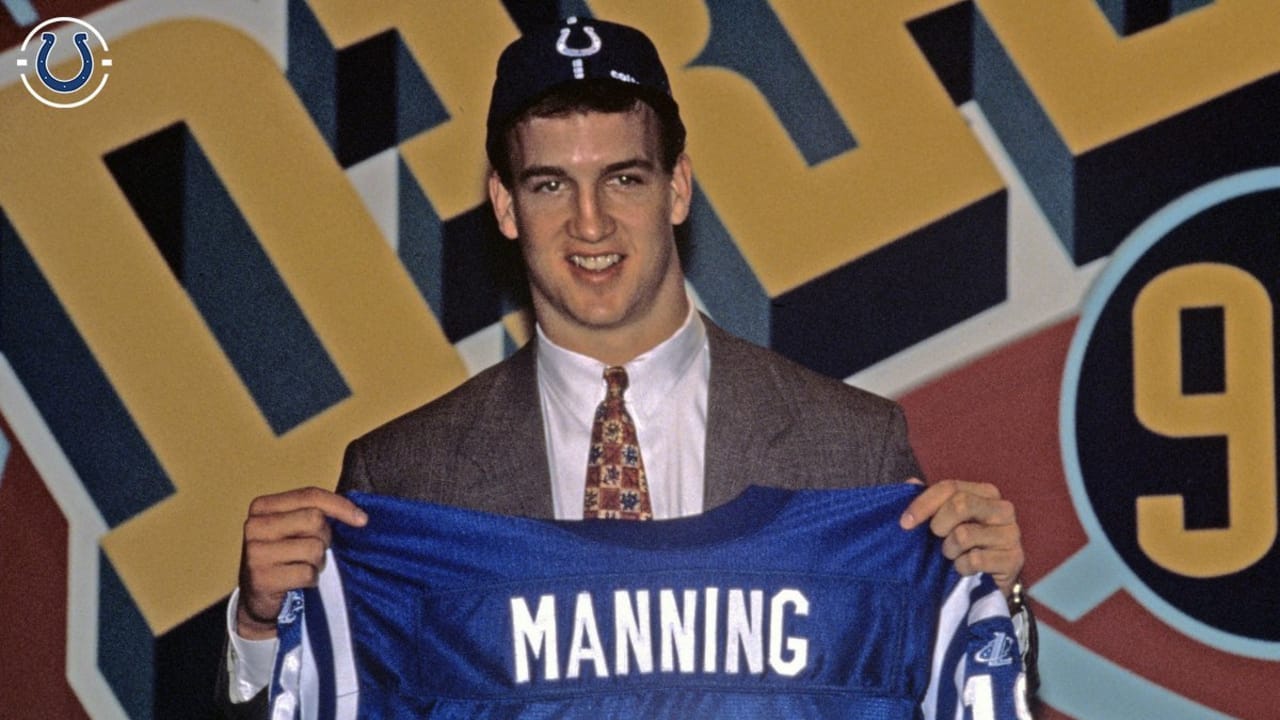

In theory, this “quarterback-savior cycle” gives bad teams a clear way back to contention. Indeed, this cycle has worked in practice for several teams over the years. The Colts used their number one overall picks in 1999 and 2012 on Peyton Manning and Andrew Luck, respectively. Both transformed the Colts from the worst team in the league to a perennial contender. Joe Burrow has done the same thing in Cincinnati. Most recently, C.J. Stroud has turned the Texans into a Super Bowl-caliber team after being drafted with the second overall pick in the 2023 draft.

Certain franchises, however, can’t seem to find their franchise quarterback, no matter how long they spend at the bottom of the NFL’s standings and the top of the draft. The Bears, Jets, and Browns have stagnated at the beginning of this quarterback-savior cycle for years. The Browns have used five first-round picks on quarterbacks since they re-entered the league, two at number one overall, and none of those players made it to a second contract with the team. Meanwhile, the league’s winningest teams have hijacked the cycle, finding their franchise cornerstones without the heavy losing seasons to yield a top-10 pick. The Packers have found generational success with quarterbacks taken at #24, #26, and #33 overall. The Ravens found two-time MVP Lamar Jackson at #32, and that’s not even to mention how the Patriots found Tom Brady at #199, and the 49ers recently got their new franchise quarterback, Brock Purdy, at #262, the final pick in the draft.

How do these franchises repeatedly find hidden gems at the most important position in the league, while teams like the Browns fail again and again, even with more valuable draft picks?

{The NFL Draft: An Even Playing Field}

It’s tempting to wonder if teams like the Packers have an evaluation edge, but the idea of prolonged success due to simply finding better prospects doesn’t hold up against the data.

As Neil Paine shows in his 2014 piece, “No Team Can Beat the Draft,” over time, no NFL team outperforms the expected career value of their draft picks. Paine explains this is because the draft is structured as a market, which is in turn driven by efficient market forces.

Like traders bidding for commodities and speculating on their relative worth, each pick a team makes is essentially a statement about how it expects a player’s career to turn out. Overvalue the commodity (i.e., draft a guy too early) and you end up with a bust; undervalue it and risk another team walking away with a prized prospect. Because of all of the effort and examination being poured into these predictions, the draft is a robust market that, in the aggregate, does a good job of sorting prospects from top to bottom.

The forces that Paine described above, where the participants in a market come together to accurately value the assets, is called the efficient-market hypothesis.

The implication of the draft being subject to the efficient-market hypothesis is that if a team consistently outperforms the draft with its quarterback choices, as the Packers have, or underperforms it, like the Browns, Jets or Bears, it likely isn’t because of superior evaluation.

That teams can repeatedly draft stars, or busts, at quarterback in an efficient market seems like a contradiction; If the Browns truly are getting repeated access to superior talents compared to the Packers, why do Green Bay’s quarterbacks continue to outperform Cleveland’s? To answer that, we’ll need to shift our focus away from how teams evaluate prospects and instead to how these teams develop them.

As a case study of an NFL team's impact on the development of their quarterback, let’s look at Zach Wilson, the second pick overall in 2021 by the New York Jets. His draft profile, by NFL.com’s Lance Zierlein, reads like this:

“Ascending quarterback prospect who possesses the swagger and arm talent to create explosive plays inside and outside the pocket. The gunslinger mentality and improvised release points are clearly patterned off of one of his favorite players, Aaron Rodgers… As with [Johnny] Manziel, too much of Wilson’s work comes off schedule due to inconsistent anticipation and a desire to hit the big play.”

Wilson is a perfect example of a high-end quarterback prospect in today’s NFL - very light on the fundamentals but heavy on the upside. Watch his tape at BYU, and you sometimes see a quarterback slinging the ball around like Aaron Rodgers or Patrick Mahomes. Other times, he’s throwing off-balance into coverage for a pick-six. In a league where quarterback play is king, the Jets gambling that they could get the good out of Zach Wilson isn’t in itself a bad bet. Rodgers and Love profiled similarly out of college, unpolished, high-upside options. The difference between the quarterbacks that the Packers got and what the Jets ended up with in Wilson is what these teams did with those quarterbacks after they acquired them.

The season before the Jets selected Wilson, they were 2-15. The Jets have been bad for a while, but this 2020 Jets team was really bad. With our powers of hindsight, we know now that the offensive group that Wilson was walking into as the day-one starter in 2021 was awful. According to Pro Football Focus, Wilson’s Jets had the 29th-graded offensive line and last-place receiving group in his rookie year.

Considering that the Jets knew Wilson was deficient in playing on time and in-rhythm, having the worst position groups at both receiver and offensive line may have been the worst possible situation for his development. The Jet’s O-Line allowed Wilson 2.5 seconds or less on a shocking 28% of his dropbacks, putting him on his back or on the run for much of the season. Compounded with a bad receiving group that didn’t win routes, there was little hope of Wilson developing any of the fundamentals in his first year with the Jets. Unsurprisingly, Wilson struggled. He threw nine TDs and eleven interceptions, finishing dead last in the league at -.029 EPA/play.

While the results were poor, the season's effect on Wilson’s long-term outlook was even worse. With no time to pass and no receivers to pass to, Wilson began bailing out of the pocket earlier and earlier and leaned more on his arm talent to try to fit the ball into razor-thin windows. Instead of developing into the Jets franchise quarterback, Wilson developed bad habits. By the end of year two, the Jets moved on. Ironically, Wilson became the backup to his hero, Rodgers.

Wilson’s time with the Jets illustrates a key weakness of leaning on the quarterback-savior cycle to lead a franchise to contention: The feature of the quarterback-savior cycle that sends the top quarterback prospects to the worst teams also means that those top prospects arrive in environments that are often the least suitable for their development. Swap Wilson’s name for Justin Fields, Mitch Trubisky, Ryan Leaf, Sam Darnold, or Johnny Manziel, and you see the same story: highly talented but unpolished prospects floundering in bad situations.

Look at the long list of busts, and it suggests that the stories that drive teams to put their faith in the quarterback-savior cycle, like Joe Burrow, Peyton Manning, or Andrew Luck, are more the exception than the rule as prospects: elite quarterbacks who developed despite a poor environment for that development.

The trick to continued NFL success isn’t landing the first pick and praying for one of these environment-proof quarterbacks. It’s navigating quarterback succession while keeping an eye on development and not falling into the fundamentally flawed quarterback-savior cycle.

You can’t talk about the success of Green Bay’s quarterbacks without mentioning the three-year apprenticeships of Aaron Rodgers and Jordan Love. Rodgers backed up Brett Favre from 2005 to 2007, and Love was Rodgers's understudy from 2020 to 2022.

Indeed, ask most Packers fans what they attribute the franchise’s good fortune at the position to, and they’ll likely point to this sitting period that both Rodgers and Love endured. Other cases of sitters, like Tom Brady and Patrick Mahomes, who both sat their first season before becoming the league’s best quarterbacks, further support that case.

But while trying to pinpoint the benefits of sitting ends up being an exercise in speculation and developmental metaphysics, the concrete lesson we can take away from Green Bay is that they’re drafting their franchise quarterbacks onto quality teams before they need them. Both Love and Rodgers were drafted by Packers teams that had been in the playoffs.

This timing was important because it enabled Rodgers and Love to play their early years on the competing rosters left behind by their predecessors. Rodgers took over a Packers team that had been to the NFC Championship the year before, with solid offensive-line play and quality weapons. Love was able to take over a Packers team that had narrowly missed the playoffs at eight wins and was a year removed from a 13-3 record and the NFC Championship.

In allowing their franchise quarterbacks to inherit these strong rosters, along with high-level offensive minds in Mike McCarthy and Matt LaFleur, the Packers' front office put Rodgers and Love in a position to develop the traits key to becoming a well-rounded NFL quarterback. That development was particularly striking with Love this past season. In his first eight games, Love led the league in interceptions and was second-to-last in completion percentage. After the first half of the year, it was fair to wonder if Love would be more Zach Wilson than Aaron Rodgers. But through LaFleur’s play-calling, behind one of the league’s best O-lines, and with a talented group of young receivers, Love drastically improved from week nine onwards. In the second half of the season, he was second in completion percentage and finished the season in the top ten of EPA/play. While Rodgers and Love profiled similarly to Wilson, their handling in Green Bay couldn’t have been more different. That helped spur strong development in their first seasons and prevented the bad habits plaguing many other highly-touted prospects from seeping into their games.

Why don’t other franchises try to replicate the methods in Green Bay? Often, they don’t have the time. As

points out in his piece on the principal-agent problem, general managers and head coaches usually have a three-year window to show results in the form of a playoff appearance; otherwise, they get fired. That short-term incentive leads to negative long-term outcomes for the franchises. General managers wind up making moves that yield instant results instead of investing in longer projects that could create sustained success.Cole goes on to say that the easiest way to solve the principal-agent problem plaguing NFL front offices is to give general managers increased job security. This is an aspect where the Packers have differentiated themselves from much of the league. Green Bay have had four GMs since 1991, with Brian Gutekunst, Ted Thompson, and Ron Wolf all enjoying tenures much longer than the league average.

With that stability at GM has come the confidence to operate on a longer time horizon. Consider the move that Thompson made to draft Rodgers or Gutekunst made to trade up to draft Love. In each case, the GM stuck his neck out by spending valuable draft capital on a player who didn’t produce anything for the team for three seasons. That isn’t a gamble general managers make if they’re worried they may be gone next year.

The Browns have taken the opposite approach from Green Bay with their general managers. At the same time that Green Bay had four GMs, Cleveland had ten - some barely lasting more than a season. The short timelines of GMs and head coaches in places like Cleveland provide a driving force behind the quarterback-savior paradox. For teams at the bottom of the league, which are the ones most likely to be hiring new GMs in the first place, these short timelines often manifest in either avoiding rookie quarterbacks out of risk aversion or taking a moonshot for a quarterback who’ll need to develop in a poor environment.

The tension between a franchise’s need for great quarterback play and the havoc that short timelines can wreak on young quarterbacks provides a key insight into avoiding the quarterback-savior cycle in the NFL: Encouraging front offices to work on longer timelines through increased stability. The Packers have taken advantage of this over the past few years, but so have other perpetual winners like the Ravens (three GMs since 1999, fifth-highest win percentage) and the Steelers (three GMs since 1999, second-highest win percentage).

Cleveland has a unique opportunity to do the same thing today. After spending years chasing a quarterback in the draft, the Browns opted to acquire an established name via trade in Deshaun Watson. This move was encouraging for Browns fans (albeit controversial) because it may set them up for a much-needed run of success over the next few years. The roster around Watson is also as good as the Browns have had for decades. But another way to look at the Watson trade is that it may finally win the front office the goodwill to look up from their short-term timelines and begin planning the moves at quarterback that could keep them competing for decades.

Edited Excellently by Greta Gruber

Research for this piece included interviews with

from and from . In addition to being kind enough to help me with this project, Seth and Nick are also two of the finest football writers on Substack, so be sure to check them out.While Favre, Rodgers, and Love were the Packers’ only day-one starters since 1992, they’ve had 7 quarterbacks start in total.

Minor edit - we didn’t introduce PFF WAR, we constructed our own version of WAR for football inspired by some baseball approaches and then Eric Eager and crew did their own for PFF WAR shortly after with a different approach (this doesn’t change the takeaway message though about positional value)

You need certain skill levels to be an NFL QB. To be elite though you need these things.

The ability to read and process defenses quickly and then deliver the ball with accuracy and anticipation.

This must be done under pressure and calmly.

Therefore quick release, good technique ( footwork) and maturity are essential.

A sense of confidence and competiveness are the essential.